Contagion Risk from Non-Invasive Ventilation

Non-invasive ventilation and high-flow nasal cannula are treatments for acute respiratory failure, including in severe cases of viral pneumonia such as COVID-19.

They are reputed to be risky techniques that spread the virus, and are banned in many hospitals for the treatment of COVID-19.

We might ask some questions about this. Where is the evidence that non-invasive ventilation (NIV) and high-flow nasal cannula therapy (HFNC) spread viral particulates or droplets? How far does this spread go? And where on the mask does the spread come from? (Could better masks that don’t cause this spread be designed?)

Here’s a look at some of the literature on the topic.

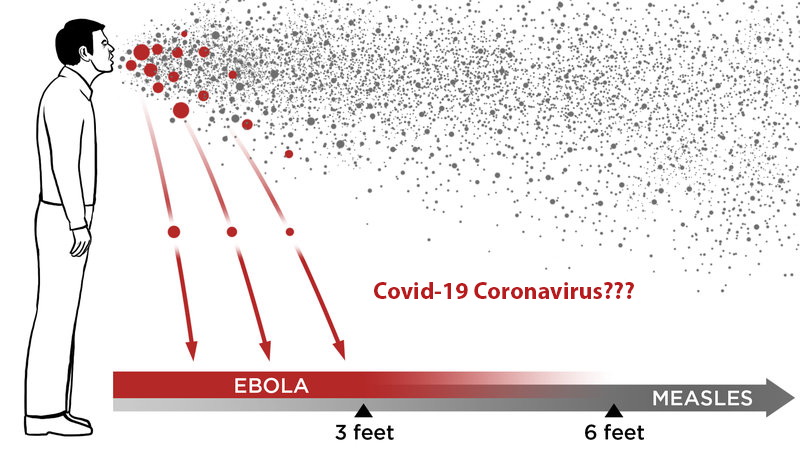

In a 5-person study of high flow nasal cannula usage, in which the participants gargled with food dye and coughed, with and without wearing a well-fitting HFNC mask, cough-generated droplets spread to a mean (standard deviation) distance of 2.48 (1.03) m at baseline and 2.91 (1.09) m with HFNC. A maximum cough distance of 4.50 m was reported when using HFNC. A separate study found that non-cough droplets extended a maximum of 62 cm when using HFNC. High-flow nasal cannula usage does spray cough droplets farther, by 0.42 m on average, than baseline.[1]

While HFNC can spread the virus farther than baseline, and farther than the 2-meter separation that’s the recommended minimum distance between COVID-19 patients in a hospital, it is unlikely to spread droplets from one room to another, for instance, through wall vents.

Non-invasive ventilation has been reported to increase the risk of viral transmission to healthcare workers in the case of SARS, but so did invasive ventilation. Oxygen therapy and NIV can disperse air up to 1M around the patient.[2] Again, this is not enough for virus particles to travel from room to room.

In a study of 628 healthcare workers treating patients with severe SARS, presence in the room during non-invasive ventilation (p < 0.01), intubation (p < 0.01), and manual ventilation before intubation (p = 0.02) were independently associated with increased risk of healthcare workers contracting SARS; in a multivariate model, the only one of these procedures that stayed significant was intubation (OR = 2.79, p = 0.004). Non-invasive ventilation and manual (bag mask) ventilation may be able to spread disease to healthcare workers, but no more so than intubation.[3]

In an experiment with noninvasive ventilation (BiPAP) with an oronasal face mask, on a dummy with a realistic model of human respiration, marking the air with smoke particles exhaled through the “airway”, smoke was found to leak from the mask through the six small exhaust holes on the nasal bridge of the mask. The smoke leaked a maximum of 0.45 M away from the dummy.[4]

In a study comparing non-invasive ventilation in normal subjects, subjects with cold symptoms, and subjects with infective exacerbations of chronic lung disease, NIV produced large (>10 um) droplets in the chronic lung disease and cold patients, but did not produce an aerosol. Due to the large size of droplets, most fall onto surfaces within 1M of the patient. Again, while healthcare workers are at risk (and need to wear personal protective equipment while treating patients with NIV) it is unlikely that NIV could send particulates into surrounding rooms.[5]

In a study sampling the air around 39 H1N1 influenza patients after various procedures, noninvasive ventilation was not associated with a significantly increased risk of finding H1N1 RNA in the air.[6]

There is room for doubt, given the evidence, whether non-invasive ventilation in fact spreads virus particles to healthcare workers. There is no evidence at all that particulates from non-invasive ventilation masks can spread more than a few meters.

References

[1] Loh, Ne-Hooi Will, et al. “The impact of high-flow nasal cannula (HFNC) on coughing distance: implications on its use during the novel coronavirus disease outbreak.” Canadian Journal of Anesthesia/Journal canadien d’anesthésie (2020): 1-2.

[2]Hui, David S. “Severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS): lessons learnt in Hong Kong.” Journal of thoracic disease 5.Suppl 2 (2013): S122.

[3]Raboud, Janet, et al. “Risk factors for SARS transmission from patients requiring intubation: a multicentre investigation in Toronto, Canada.” PLoS One 5.5 (2010).

[4]Hui, David S., et al. “Noninvasive positive-pressure ventilation: an experimental model to assess air and particle dispersion.” Chest 130.3 (2006): 730-740.

[5]Simonds, A. K., et al. “Evaluation of droplet dispersion during non-invasive ventilation, oxygen therapy, nebuliser treatment and chest physiotherapy in clinical practice: implications for management of pandemic influenza and other airborne infections.” Health technology assessment (Winchester, England) 14.46 (2010): 131-172.

[6]Thompson, Katy-Anne, et al. “Influenza aerosols in UK hospitals during the H1N1 (2009) pandemic–the risk of aerosol generation during medical procedures.” PloS one 8.2 (2013).