Oxygen Supplementation 101

COVID-19 causes shortness of breath and in severe cases requires artificial ventilation. There is a shortage of mechanical ventilators in hospitals, and a shortage of medical personnel to treat patients with severe COVID-19, so there’s widespread interest in contributing to open source ventilation projects. For these efforts to be effective, though, we need to understand what COVID-19 patients need in terms of ventilators and other supplemental oxygen sources.

COVID-19 Symptoms and Clinical Guidelines

Most patients who go to a hospital for COVID-19 have pneumonia or infection of the lungs, which is visible on a chest X-ray. A large fraction (41.3%) receive supplemental oxygen therapy; a smaller fraction (5%) needed to be admitted to the ICU, and 6.1% needed mechanical ventilation.[1]

ARDS Severe cases of COVID-19 result in developing Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome (ARDS). Fluid builds up in the lungs; the lungs may collapse; blood oxygen drops; and mechanical ventilation is required. Merely providing air with a higher oxygen content than room air isn’t enough; pressure needs to be administered to keep the alveoli open.

Oxygen Therapy: Bag Mask

A bag valve mask is used in emergencies and for temporary ventilation while preparing for intubation.

Here is a doctor demonstrating how to use a bag valve mask.

Oxygen Therapy: Nasal Cannulas and Simple Masks

When a patient has difficulty getting enough oxygen but can breathe on their own, they get oxygen therapy. That is, they’re given a supply of air with an increased concentration of oxygen, but without any additional pressure.

Oxygen can be administered non-invasively through a nasal cannula or a simple mask. This can safely be done outside a hospital setting. Oxygen concentrators are standard to keep in the home for people with chronic lung conditions like emphysema and COPD. Simple oxygen masks are regularly used by non-medical rescue personnel like firefighters and lifeguards.

Oxygen Concentrators

To produce a supply of filtered, high-oxygen air from room air, you need an oxygen concentrator, which removes nitrogen from the air through filters. This oxygen-enriched air can then be provided to the patient through a mask or nasal cannula.

Home oxygen concentrators are available with a prescription.

Oxygen Therapy: Non-Rebreather Masks A non-rebreather mask is an oxygen mask with a sealed bag that prevents inhalation of room air or previously exhaled air, which allows for higher concentrations of oxygen to be administered.

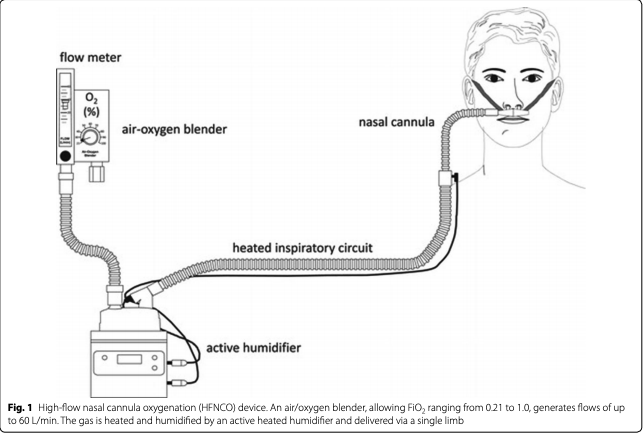

Oxygen Therapy: High Flow Nasal Cannula

[5]

A high flow nasal cannula provides a higher flow of oxygen, and warms and humidifies it, so that it is less irritating to mucous membranes and easier for the patient to breathe. The higher flow also increases ventilation and causes the patient to rebreathe less exhaled air, which increases ventilation (the elimination of CO2). It also provides a small amount of PEEP (positive end-expiratory pressure, keeping the alveoli open) which can be helpful for patients whose lungs are collapsing due to respiratory failure.

High-flow nasal cannulas will aerosolize the COVID-19 virus, infecting everyone nearby. They are not allowed in hospitals for COVID-19 because they spread disease.

Noninvasive Ventilation: CPAP and BIPAP

CPAP machines keep the patient’s airway open by forcing air continuously through a mask. It is usually used for sleep apnea and other conditions that cause difficulty breathing. The patient must initiate all breaths, but has additional pressure support to keep the airway and alveoli open.

BIPAP machines work the same way, except that they have two pressure settings instead of just one: a higher pressure for inhalation and a lower one for exhalation.

BIPAPs and CPAPs can be used safely at home and don’t need medical supervision.

Like high-flow nasal cannulas, CPAP and BIPAP machines aerosolize the COVID-19 virus and are an infection risk for everyone nearby. They are not allowed in hospitals for COVID-19; they will spread disease. (Source: doctor interview.)

Invasive Mechanical Ventilation for ARDS

When the alveoli can’t stay open on their own, supplemental oxygen isn’t enough; this is when the patient needs to be intubated and placed on a ventilator that can provide enough pressure to keep the airway and alveoli open, so gas exchange can occur and the blood can be oxygenated.

The pressure on a mechanical ventilator needs to be precisely calibrated to the patient. Too much pressure and the lung can tear; too little, and the patient’s blood will fill with CO2 and not get enough oxygen. This is one reason why patients need to be placed on ventilators by trained experts (typically ICU nurses, doctors, and respiratory therapists).

Another reason is that intubation is an invasive procedure; an endotracheal tube is inserted into the airway, which requires sedatives and anaesthetics to avoid pain and the gag reflex. Mistakes with aiming the tube or dosing the medications could cause permanent injury or death.

You don’t want an untrained person sticking this blade down someone’s throat!

How Effective Is Outpatient Oxygen Therapy or Noninvasive Ventilation?

There are multiple projects underway to produce open-source oxygen therapy or non-invasive ventilation devices for COVID-19. Are these projects actually useful?

They’re not going to be used in hospitals, because of the risk that they’ll spread infection. But could they still be useful for patients self-quarantining at home, in a context where ICU beds and ventilators are scarce?

In other words, how often do patients who need non-invasive ventilation go on to need invasive ventilation, how long does it take before they need to escalate to invasive ventilation, and how helpful is non-invasive ventilation in preventing the need for invasive ventilation?

In 310 patients with acute respiratory failure in ICUs (typically due to pneumonia), randomized to standard oxygen therapy in a nonrebreather mask, oxygen therapy in a high flow nasal cannula, or noninvasive ventilation, there was no significant difference in the intubation rate (30-40% needed intubation within 4 days). However, the high-flow oxygen group had a significantly lower 90-day mortality rate than the other two groups: 7% of the high-flow oxygen group died within 90 days, compared to 28% on standard oxygen and 23% on non-invasive ventilation. The high-flow oxygen group also had significantly better blood oxygenation and spent fewer days on ventilators than the other two groups.[3] High-flow nasal cannulas were also more effective than conventional oxygen masks at avoiding the need for repeated ventilation, in another randomized trial.[4]

So, suppose you’re a person with respiratory failure, but you have an oxygen mask, CPAP, BIPAP, or high-flow nasal cannula at home. 40% of the time or so, your noninvasive home equipment is going to fail and you’ll need to be intubated. Usually this happens quite urgently; if you need to take an ambulance to get to the hospital it might be too late.

Since NIV (noninvasive ventilation) does not significantly reduce the risk of needing intubation, it’s strictly inferior to have people on NIV at home (where they may not be able to get to a doctor in time if their condition worsens) than to have them on conventional nonrebreather oxygen masks in the hospital (where they can get an emergency intubation if their condition worsens.) The improved mortality stats for high-flow nasal cannula are probably swamped by the increased risk associated with being at home and not being able to get an emergency intubation quickly.

Therefore, building open-source CPAP, BIPAP, or high-flow nasal cannulas is not valuable for COVID-19, in any world where ICUs and ventilators are still available.

If the situation deteriorates so badly that most people can’t go to ICUs at all, non-invasive home ventilation may be better than nothing, but it’s not the top priority for increasing capacity to respond to the COVID-19 pandemic.

Existing Ventilator Design Projects

I’ve seen a lot of links to projects to design open-source ventilators to handle the current ventilator shortage. Many of these are automated bag masks, or CPAPs, which aren’t recommended for use in hospitals because they spread COVID-19; and they won’t work on the more severe cases of respiratory distress anyway. Only two projects that I found, the Pandemic Ventilator and the Flometrics project, are explicitly trying to match the specifications of the type of mechanical ventilators found in ICUs.

A hospital in Italy, after being unable to source valves for Venturi oxygen masks, got emergency supplies from a local 3D printing company.

While this is a worthwhile project, it is of course just a single part for an oxygen mask, not a ventilator.

Auto Bag Ventilator – a Rice University engineering student designed a low-cost, automatically pumping bag ventilator for low resource settings.

This is a type of ventilator for very short term use, in first aid emergencies. It is not a substitute for a mechanical ventilator because there is no way to calibrate the pressure exactly. (A mechanical ventilator needs to be accurate to within at least 0.001 psi.)[6]

It is also not safe for COVID-19 in hospital settings because of the risk of aerosolization.

This is a low cost mechanical ventilator based on a Shopvac, designed by one of the patent holders for the Phillips Espirit ventilator.

This is the kind of thing that is designed to substitute for the mechanical ventilators used in ICUs, and could be very valuable if it works.

Low-Cost Open Source Ventilator

This is a design for a modified CPAP machine for non-invasive ventilation. That means it’s not going to be usable in hospitals because of disease spread issues, and ~40% of the time, a person with COVID would need to escalate to intubation within a few days anyway.

Low-Cost Portable Mechanical Ventilator – this is an MIT student project.

This too is a bag ventilator equipped with a mechanical pump; therefore, not usable for COVID-19 in hospital settings.

They claim to have a low-cost (<$300) ventilator design and are capable of training staff and deploying the devices. Unclear what type of device this is.

OneBreath Ventilators This Stanford-founded company is working to develop a low cost ICU ventilator for use in the developing world. These could be suitable for severe COVID-19 cases.

They are not yet available for sale but they are open to outreach, info@onebreathventilators.com.

Another motorized Ambu-bag. Again, these are not designed to be used for more than 10 hours at a time & won’t work for ARDS.

This is a project to build a mechanical ventilator for ARDS. They also have a blog at https://panvent.blogspot.com/

This is the type of thing that could potentially be valuable for severe cases of COVID-19; it’s meant to substitute for the type of mechanical ventilators that are currently in short supply. Any new, rapidly developed machine will not meet regulatory approval standards in the US, but in emergencies or in countries with less stringent laws, an unapproved (but functional) machine may be better than nothing.

This ventilator is designed to be deployed in hospitals, specifically in rural Latin America. It is not for home care.

The Ventilator Project This is a group from NECSI, the New England Complex Systems institute, working to

a.) increase production of ventilators by existing manufacturers

b.) work on open-source plans for building ventilators for hospitals

c.) regulatory efforts to approve hospitals to use emergency ventilators

Current Shortages of Oxygen & Breathing Equipment

Oxygen Concentrators

Oxygen concentrators were in short supply even before the pandemic – a June 2019 article notes that half of people who use portable oxygen supplies had problems with broken equipment or inadequate supplies of oxygen.[7]

Ventilators

In a pandemic crisis, New York State is predicted to be short 15,783 mechanical ventilators a week at the peak of the outbreak.[8]

Evidence that Non-Invasive Ventilation Spreads COVID-19

An ICU in Hong Kong gave guidance against bag mask ventilators:

We recommend avoiding bag mask ventilation for as long as possible; and optimising preoxygenation with nonaerosol-generating means. Methods include the bed-up-head-elevated position, airway manoeuvres, use of a positive end expiratory pressure valve, and airway adjuncts. If manual bagging is required, we suggest gentle ventilation via a supraglottic device instead of bag mask ventilation.[9]

The same guidelines were implemented by the largest acute care hospital in Singapore: Infection prevention entails reducing aerosol-generating procedures (i.e., airway manipulation, face mask ventilation, open airway suctioning, patient coughing) as far as possible…Non-invasive positive pressure ventilation and high flow nasal cannulae such as the transnasal humidified rapid-insufflation ventilatory exchange should be avoided to reduce the risk of viral aerosolization…Venturi masks should be avoided as they may aerosolize the virus.

References

[1]Guan, Wei-jie, et al. “Clinical characteristics of coronavirus disease 2019 in China.” New England Journal of Medicine (2020).

[2]Murthy, Srinivas, Charles D. Gomersall, and Robert A. Fowler. “Care for Critically Ill Patients With COVID-19.” JAMA (2020).

[3]Frat, Jean-Pierre, et al. “High-flow oxygen through nasal cannula in acute hypoxemic respiratory failure.” New England Journal of Medicine 372.23 (2015): 2185-2196.

[4]Hernández, Gonzalo, et al. “Effect of postextubation high-flow nasal cannula vs conventional oxygen therapy on reintubation in low-risk patients: a randomized clinical trial.” Jama 315.13 (2016): 1354-1361.

[5]Papazian, Laurent, et al. “Use of high-flow nasal cannula oxygenation in ICU adults: a narrative review.” Intensive Care Medicine 42.9 (2016): 1336-1349.

[6]http://www.ardsnet.org/files/ventilator_protocol_2008-07.pdf

[7]https://www.statnews.com/2019/06/14/access-lifesaving-oxygen-therapy/

[8]https://www.nytimes.com/2020/03/17/nyregion/ny-coronavirus-ventilators.html

[9]Cheung, Jonathan Chun-Hei, et al. “Staff safety during emergency airway management for COVID-19 in Hong Kong.” The Lancet Respiratory Medicine (2020).