Aging Interventions from Older Publications that Deserve a New Look

Why Read Old Papers?

These days, from what I’m told by knowledgeable people, there’s a fairly tight feedback loop between current aging research and the biotech industry. When a new, major aging-related paper comes out, there are people seriously evaluating whether they can start a company around it. But that isn’t necessarily true when it comes to old research. There’s no automatic means by which old papers “go viral.” There are no conferences (that I know of) where people call their colleagues’ attention to remarkable, decades-old results that haven’t received follow-up investigation.

I think old papers deserve a second look, for a few reasons.

1.) Often a result that had little interpretability or applicability in the past can benefit from contemporary tools. Let’s say, twenty years ago researchers found a way to extend life in rats – but it was a surgical operation that would be too invasive or risky to try on healthy humans. And maybe that was the end of that research direction. But now we have lots of new options! We can take tissue samples with and without the intervention, and look at gene and protein expression, even down to the individual cell level. We can identify genetic modifications or drug targets that could be used to simulate the intervention in a safer, more targeted way.

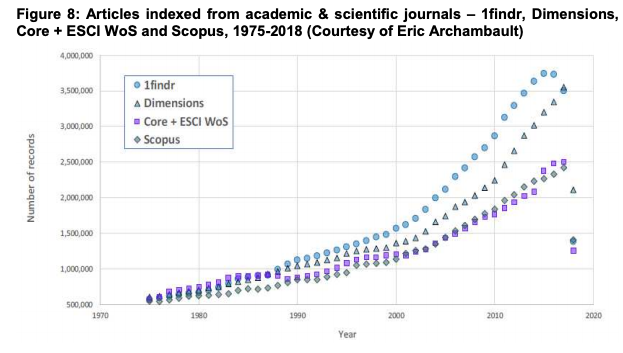

2.) Looking at old papers reduces some of the biases that come from looking at the latest, most-cited papers. The volume of scientific publications is increasing at an exponential rate, up to 4% a year.[1]

However, the reliability of the average publication has probably decreased. If there are indeed “diminishing returns to science” in recent decades, as Patrick Collison and Michael Nielsen argue [2], with roughly constant rates of important discoveries (as rated by experts) and flat economic productivity (a measure that we’d expect to correlate with technological progress) despite exponentially growing numbers of scientists, publications, and dollars devoted to science, then the quality of the average paper, scientist, or dollar allocated to research must have gone down. In that case, a randomly chosen older paper should be more trustworthy than a newer paper.

One might counter that the new papers that get the most attention aren’t randomly chosen – they’re the highly cited papers, or the papers in prominent journals. Maybe the average paper has gotten worse, but the average is being pulled down by junk papers in journals so low-quality and obscure that barely anybody reads them; so, perhaps, the typical new paper that a colleague (or your twitter feed) brings to your attention is no less credible than a comparable old paper.

I think that optimistic outlook is doubtful; in fact, articles in prestigious (high-impact-factor) journals are more likely than average to be retracted, and many measures of research reliability anticorrelate with impact factor, implying that articles the most prestigious journals are less trustworthy than average[3]:

- overestimating effect size in gene-association

studies increases with impact factor (more bias in more prestigious journals)

-

sample size in gene-association studies decreases with impact factor

-

statistical power in psychology and cognitive science papers decreases with impact factor

-

randomization in animal studies is reported less frequently in papers from high-impact-factor journals

-

errors in supplemental data (eg Excel auto-converting a gene name to a date) are more common in papers from high-impact-factor journals

-

p-value reporting errors, usually in the direction of misinterpreting a non-significant result as significant, are more common in papers from high-impact-factor journals

-

metrics to identify tell-tale signs of questionable research practices find lower research quality in higher-impact-factor journals.

So, no, we can’t assume that the most-cited papers of today are the cream of the crop. If anything, there’s more pressure today than ever to get dramatic but untrustworthy results, and that pressure is highest at the most competitive journals.

One way to reverse this effect is to go back in time. If the amount of noise in the system is increasing, an old paper is more likely to have a valid signal than a new one.

3.) Low technology can be a blessing in disguise.

The miracle of modern molecular biology is that we keep developing better tools to affordably do breadth-first searches. “Sequence ALL the genes!” “Quantify ALL the transcripts!” “Quantify ALL the proteins!” And so on. The danger of having these incredible tools is that you can cherrypick positive results – and people do.

It’s much harder to erroneously get an apparently therapeutic intervention if your tools are blunter and your search space is smaller. If somebody in 1944 says that shining light on a duck’s head makes its testes grow[4], then by gum I bet that actually happens!

Because it’s not coming from a breadth-first search, somebody had to have a specific reason to think that the experiment would work, and because there just aren’t that many experiments being done at random, you can expect that to be a well-informed reason. The prior is higher.

There’s a similar sense in which lack of standardization is a blessing in disguise. Most mammal experiments today are done on the same handful of strains of inbred mice, for instance. The standardization is a boon to researchers in many ways (you can make apples-to-apples comparisons, you don’t have to spend time inventing the basics of experimental methods yourself) but it also means that experimental results can just turn out to be an artifact of the “standard methodology.” Looking at older experiments, which have greater diversity in model organisms and other experimental methods, can be a corrective.

4.) Old papers are undervalued opportunities.

The author of the latest exciting result is a ready-made advocate for the discovery and a potential founder or collaborator for new ventures to put it into practice. The author of an old paper, by contrast, might be dead or retired, with nobody to champion the potential applications of the discovery. It’s very easy for an area of research to quietly fall out of fashion through no inherent lack of merit, just because it never met the right opportunity for application.

I’m just barely old enough to remember when neural nets were thought of as an embarrassing phase in the history of computer science; they became “hot” again in 2012, with AlexNet, when newly affordable GPUs proved that deep learning algorithms could suddenly outperform the competition. In other words, advances in a totally different technology made a “failed” research approach into an overnight success.

Going through old, not necessarily well-known experiments to see if there are opportunities is something I don’t believe is being done that often, and is probably an unusually good place to apply a little bit of time and attention for big returns.

That said, let’s look at some specific examples! These are all results from prior to the year 2000, that are experimental interventions affecting vertebrate lifespan or aging, and which aren’t currently the focus of a research program that I’m aware of.

Lowering Body Temperature: 71% Life Extension in Fish

Unusually long-lived vertebrates (tortoises, sharks, rockfish, etc, which can survive for centuries, or naked mole rats, which are extremely long-lived for their size) are frequently cold-blooded. Warm-blooded animals which are long-lived (in absolute terms, like whales, or relative to their size, like bats, hummingbirds, and squirrels) often undergo temporary reductions in body temperature, during diving or hibernation. Moreover, interventions like dietary restriction which extend lifespan have the effect of reducing body temperature. So can reducing body temperature directly extend life?

For a cold-blooded example, transferring fish from 20-degree water to 15-degree water extended lifespan by 71%, in a 1972 study.[5]

To reduce the body temperature of a warm-blooded animal, it’s not enough to reduce ambient temperature, since warm-blooded animals generate heat to compensate. In fact, reducing the ambient temperature actually shortens mouse lifespan. However, there are tricks to lower body temperature in a warm-blooded animal.

Mice genetically modified to overexpress the uncoupling protein, UCP2, in the hypothalamus have lower body temperature than wild-type[6], and they live longer than their wild-type counterparts (20% increase in female median lifespan, 12% in male.)

You can also induce hypothermia by stimulating the heat-detecting cells in the hypothalamus, either by injecting capsaicin [7], heating the hypothalamus directly with a thermode [8], or stimulating the heat-sensing neurons optogenetically [9].

The natural next experiments to do are a.) see if any of these other methods of inducing hypothermia affect lifespan and diseases of aging in mice or other mammals; b.) do longitudinal transcriptomics or other broad assays to see what reduced body temperature is doing and whether its effects can be simulated chemically or genetically.

Altered Photoperiod Cycle Length: Short “Years” Shorten Lifespan 30% in Lemurs

Days get longer in summer and shorter in winter; by lengthening or shortening the cycle of alteration in photoperiod length (by changing artificial lighting) you can give an animal a shorter or longer subjective “year”. This turns out to affect lifespan!

The gray mouse lemur is a prosimian primate, native to Madagascar, that is long-lived for its size. During the long-day summer, gray mouse lemurs breed and are more active; during the short-day winter, they gain weight, become lethargic, and don’t copulate. If you alter the photoperiod cycle artificially, you can alter the timing of these behavioral and morphological changes accordingly – and if you reduce the “year length” by a third, from 12 months to 8 months, lifespan also shortens by 30% and the onset of white fur happens 30% earlier. [10] . In other words, lemurs live 9-10 “subjective years”, whether those are 8-month years or 12-month years.

The obvious follow-up experiment is to go the other direction – do lemurs (or other animals) live longer if you subject them to 16-month subjective years? And to take some tissue and blood samples and try to identify how this effect works – do we see pathological changes, transcriptional changes, hormonal changes, metabolic changes?

Constant Light Exposure: 25% Life Extension in Hamsters

A Syrian hamster model of congenital heart disease showed delayed onset of heart failure and 25% life extension if they were kept in continuously lit conditions.[11] The obvious corollary studies are to take heart tissue samples and blood samples and look for altered gene expression or metabolic parameters that might explain the effect of light exposure on preventing heart failure. It also might be possible to experiment directly with continuous light exposure on humans, since it’s probably not dangerous.

Pineal-Thymus Graft: 24% Life Extension in Aged Mice

Implanting the pineal gland of a young mouse into the thymus of an old (16-22 month) mouse extends lifespan 19% in C57BL6 mice, 20% in Balb/c mice, and 35% in hybrid mice, for an average of 24% overall.[12] This is consonant with a more extensive literature about the pineal gland or the main hormone (melatonin) it secretes having a life-extending effect through preventing the dysregulation of the circadian rhythm which occurs with age. The obvious follow-up study to do is a replication of the same implantation experiment, along with longitudinal expression data, to find out how this works and work towards identifying how a similar effect could be replicated by a less invasive intervention.

Splenectomy: 19% Life Extension in Aged Mice

In a 1969 experiment, adding spleen cells to mice of the same age as the cell donors shortened lifespan; adding spleen cells from younger mice (14 week) to older mice (76 week) extended median lifespan from 105 weeks to 128 weeks, a 13% lifespan effect; and removing the spleens of mice altogether at age 97 weeks increased median remaining lifespan from 118 to 158 weeks, a 19% lifespan effect.

Clearly, the aged mouse spleen contains some factor that accelerates age-related decline. The obvious question is to find out what this is, through expression or proteomics studies on young, aged, and splenectomized mice, and see if there’s a way to target the culprit pharmacologically.

Induced Hypothyroidism: 17% Life Extension in Rats

Exposing newborn rats to thyroid hormone permanently reduces their bodyweight and thyroxine levels; it’s a way of artificially inducing hypothyroidism.[13] It also has the effect of dramatically elevating their prolactin levels; as prolactin is stimulated by TSH release from the hypothalamus, clearly neonatal T4 exposure doesn’t prevent TSH release in the brain, but rather impairs the thyroid’s ability to respond to it. This induced hypothyroidism also extends median lifespan by 17% and maximal lifespan by 6%. Obviously, inducing hypothyroidism isn’t a viable intervention for humans, but looking at changes in hormone levels and gene regulation in induced hypothyroidism might give clues to what downstream mechanisms are responsible for the lifespan increase and whether there’s a less-side-effect-heavy way to induce it.

Castration: 17% Life Extension in Rats

Removing the testes of male Wistar rats has been found to extend lifespan 17% relative to unbred intact males; removing the ovaries extends lifespan 29% relative to unbred females. [14] This isn’t too surprising given that caloric restriction (a reliable life-extending intervention in rodents under typical lab conditions) has antigonadal effects, and that extremely dramatic lifespan effects can come from removing the germ cells in C. elegans.[15] There’s also some correlational evidence – for instance, castrated male cats arriving at veterinary hospitals lived 67% longer than intact males.[16]

Obviously, castration isn’t a practical intervention for most humans, but it’s possible that there’s some downstream effect that doesn’t alter fertility or observable sex characteristics and preserves some of the anti-aging effect; this is a good opportunity for looking at longitudinal expression changes in castrated vs. intact animals and trying to identify the mechanism of lifespan extension.

Lateral Hypothalamic Stimulation: 5% Life Extension in Aged Rats

Stimulating the lateral hypothalamus is pleasurable, and animals given the opportunity to self-stimulate will do so; this is what’s known as wireheading. Interestingly enough, there are interactions with aging here as well. Young adult rats have more neurons and more electrical activity in the lateral hypothalamic area (LHA) than old rats; young rats also exhibit more self-stimulatory behavior than old rats when given access to a button that turns on the electrode. Moreover, in old rats, chronic stimulation in the LHA extended lifespan from 1075 days to 1125 days (5% of total median lifespan, 8% of total maximum lifespan, 35% of residual lifespan); stimulation reduced body mass as well.[17] Is this just a dietary restriction effect, or is it something else? The natural thing to do is to try the experiment again, this time compared against controls given the exact same amount of food to eat; and also, to take brain samples after death and possibly other blood samples during lifespan to try to identify metabolic or regulatory changes caused by the stimulation.

Blindness: Increases Survival in Rats

Blindness affects the circadian rhythm; it effectively gives the same hormonal signals as perpetual darkness. Rats blinded at 25 days had increased lifespan relative to controls; at 748 days, when the experiment concluded, the blind rats had a 95% survival rate while the control rats had a 50% survival rate. The natural follow-up is to do a full lifespan study so we can get an actual measurement of the effect on median lifespan, as well as measurements of other biomarkers so we can identify a mechanism and possibly a way to replicate the anti-aging effect without actually inducing blindness.

Fetal Hypothalmic Graft: Restores Fertility and Circadian Rhythm in Rats and Hamsters

In keeping with the pattern of neuroendocrine effects on aging, it turns out that transplanting the suprachiasmatic nucleus (the part of the hypothalamus responsible for entraining the circadian rhythm in response to day length) from fetal animals into the brains of aged animals can restore the periodicity of the circadian rhythm and restore diminished fertility. With age, circadian rhythms become less regular; animals wake more during the periods when they should be sleeping, and/or are more lethargic during the periods when they should be awake. Fetal SCN grafts reverse this phenomenon in both hamsters [18] and rats.[19] Moreover, 7 of 10 aged rats given fetal anterior hypothalamus transplants regained fertility and fathered a total of 106 pups[20], while medial basal hypothalamus transplants from rat fetuses into aged female rats reversed hypogonadism.[21]

The hypothalamus regulates a variety of hormonal signals, which become dysregulated with age; it seems that some of these effects can be reversed by transplanting a younger hypothalamus. The most natural question to ask is, first, does this extend life? Second, can we identify on the genetic or molecular level what the younger hypothalamus tissue is doing that improves aging-related phenotypes? If so, there might be a non-invasive way to replicate the effect.

What Now?

These are ten very broad suggestions for animal experiments to run, which might yield targets that are ripe for intervention. I’d expect, without looking too deeply into details, that each of these ten experiments would have a 6-figure price tag. And I’m aware of nobody who’s working on these projects (please correct me if I’m wrong!)

Could these projects turn into biotech companies? It’s hard to say, of course; it depends on whether the experimental results are good, among other things. But I’m pretty inclined to believe that we don’t know all the aging-modulating targets yet. That points to phenotypic screening approaches (like what we’re doing at Daphnia Labs) or target-discovery studies (like the ones proposed in this post, or like the ones being done at Gordian, BioAge, or Fauna), being quite valuable. We don’t know everything that’s out there, and early-stage exploration is a lot cheaper than depth-first drug development, so on the margin more exploration is a “good buy”, it seems.

References

[1]https://www.stm-assoc.org/2018_10_04_STM_Report_2018.pdf

[2]https://www.theatlantic.com/science/archive/2018/11/diminishing-returns-science/575665/

[3]Brembs, Björn. “Prestigious science journals struggle to reach even average reliability.” Frontiers in human neuroscience 12 (2018): 37.

[4]Benoit, Jacques, and L. Ott. “External and internal factors in sexual activity: effect of irradiation with different wave-lengths on the mechanisms of photostimulation of the hypophysis and on testicular growth in the immature duck.” The Yale journal of biology and medicine 17.1 (1944): 27.

[5]Liu, R. K., and R. L. Walford. “The effect of lowered body temperature on lifespan and immune and non-immune processes.” Gerontology 18.5-6 (1972): 363-388.

[6]Conti, Bruno, et al. “Transgenic mice with a reduced core body temperature have an increased life span.” Science 314.5800 (2006): 825-82

[7]Jancsó-Gábor, Aurelia, J. Szolcsanyi, and N. Jancso. “Stimulation and desensitization of the hypothalamic heat‐sensitive structures by capsaicin in rats.” The Journal of physiology 208.2 (1970): 449-459.

[8]Hammel, H. T., J. D. Hardy, and MiM Fusco. “Thermoregulatory responses to hypothalamic cooling in unanesthetized dogs.” American Journal of Physiology-Legacy Content 198.3 (1960): 481-486.

[9]Zhao, Zheng-Dong, et al. “A hypothalamic circuit that controls body temperature.” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 114.8 (2017): 2042-2047.

[10]Perret, Martine. “Change in Photoperiodic Cycle Affects Life Span in a Prosimian Primate (Microcebus murinus.” Journal of biological rhythms 12.2 (1997): 136-145.

[11]Tapp, Walter, and Benjamin Natelson. “Life extension in heart disease: an animal model.” The Lancet 327.8475 (1986): 238-24

[12]Pierpaoli, Walter, et al. “The pineal control of aging: the effects of melatonin and pineal grafting on the survival of older mice.” Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences 621.1 (1991): 291-313.

[13]Ooka, Hiroshi, Saori Fujita, and Emiko Yoshimoto. “Pituitary-thyroid activity and longevity in neonatally thyroxine-treated rats.” Mechanisms of ageing and development 22.2 (1983): 113-12

[14]Asdell, S. A., and S. R. Joshi. “Reproduction and longevity in the hamster and rat.” Biology of reproduction 14.4 (1976): 478-480.

[15]Hsin, Honor, and Cynthia Kenyon. “Signals from the reproductive system regulate the lifespan of C. elegans.” Nature 399.6734 (1999): 362.

[16]Hamilton, James B. “Relationship of castration, spaying, and sex to survival and duration of life in domestic cats.” Reproduction and aging. New York, NY: MSS Information Corporation (1974): 96-115.

[17]Frolkis, V. V., et al. “The lateral hypothalamic area: Peculiarities of aging and the effect of chronic electrical stimulation on the lifespan in rats.” Neurophysiology 32.4 (2000): 276-282.

[18]Viswanathan, N., and F. C. Davis. “Suprachiasmatic nucleus grafts restore circadian function in aged hamsters.” Brain research 686.1 (1995): 10-16.

[19]Li, Hua, and Evelyn Satinoff. “Fetal tissue containing the suprachiasmatic nucleus restores multiple circadian rhythms in old rats.” American Journal of Physiology-Regulatory, Integrative and Comparative Physiology 275.6 (1998): R1735-R1744.

[20]Huang, H. H., J. Q. Kissane, and E. J. Hawrylewicz. “Restoration of sexual function and fertility by fetal hypothalamic transplant in impotent aged male rats.” Neurobiology of aging 8.5 (1987): 465-472.

[21]MATSUMOTO, Akira, et al. “Recovery of declined ovarian function in aged female rats by transplantation of newborn hypothalamic tissue.” Proceedings of the Japan Academy, Series B 60.4 (1984): 73-76