Genes Involved in Aging -- Looking For Intersections

A natural type of question you might ask, if you’re interested in understanding aging, is which genes are involved in the aging process. The practical upshot of identifying genes with causal roles is that they’re potential drug targets. If diseases of aging are caused or worsened by the excess of some protein, you might want to inhibit the production or activity of that protein. If diseases of aging are caused or worsened by a deficit in some protein, you might want to stimulate its production. We have a lot of different kinds of experiments that can be run for identifying what genes and proteins are involved in aging, and thus a lot of aging-related “omics” studies. I’ll briefly summarize a few categories I know about.

Longitudinal Transcriptomics You can compare the expression of genes in tissue samples from old vs. young organisms (humans or mice) and see which genes are expressed more or less with age. Today it’s even possible to get single-cell resolution on gene expression; we can identify the rate of gene transcription for each gene in a specific cell at a given time. Similarly, you can get proteomics data, directly measuring the quantity of each protein in a tissue sample. This gives us correlational information about which genes are altered in the aging process, in particular tissues and cell types. It doesn’t by itself tell us which interventions might prevent disease. If a particular gene is more expressed with age, it could be because it’s a cause of some deleterious process, or because it’s a symptom of that process, or because it’s part of the body’s attempt to mitigate that process. Whether you want to inhibit that protein’s activity or production depends on what it’s doing, and expression levels by themselves can’t tell you that.

Comparative Genomics Animals don’t all age in the same way. Some are exceptionally long-lived, either in absolute terms (whales, elephants, tortoises, rockfishes, the Greenland shark) or relative to their size (bats, naked mole rats). Some mammals are immune from cancer. Can we identify “genes responsible for healthy longevity” in the animal kingdom? Could we “borrow” the adaptations that slow-aging animals have developed, as treatments for humans? Given the genomes for two species, you can identify homologous genes – genes that have very similar sequences and probably similar functions. Something like half our genes have homologues in common with insects and all vertebrates.

If the homologue of a gene in an exceptionally long-lived species is absent or has a loss-of-function mutation, you might ask whether that gene contributes to aging.

If a gene family of similar proteins is “expanded” in a long-lived species (meaning there are more variations on that gene present) or if a gene has a high copy number (meaning there are many identical versions of that gene) you might ask whether that gene has a protective effect.

If a gene shows evidence of positive selection in a long-lived species, you might ask whether that gene has a protective effect against some aging process.

If there’s a correlation between copy number or gene family size and lifespan (or lifespan per body weight) across species, that’s somewhat stronger evidence that there’s an association between those genes and lifespan.

Again, these are all correlational; they don’t tell you how the gene works, or what would happen if you interfered with it experimentally.

Experimental Genetic Modifications If you induce a genetic mutation in a mouse gene and the mouse lives longer or avoids the onset of age-related diseases, then you do have causal evidence that the gene is involved in regulating aging. There are a variety of ways of inducing specific mutations, some permanent and some temporary, some causing total absence of the gene (knockout) while others cause a deficit (knockdown) or unusually high production of the gene product (overexpression.) Looking for the Intersection Most broad studies (longitudinal transcriptomics, comparative genomics) looking for genes involved in aging come up with totally different lists of candidate genes. Sometimes, of course, this is expected, because they’re looking at different tissues or different organisms. You don’t expect all animals or all tissues to change in the same way with age. And, of course, comparing genomes between species and comparing gene expression over time within one species are apples-to-oranges comparisons.

But even in cases where the experiments are supposed to measure the same thing, there’s poor replication. And that’s not surprising because the samples are so small. It’s not uncommon to see longitudinal transcriptomics studies with fewer than ten organisms in the “old” and “young” groups.

And this matters because if you want to have any hope of translation to humans, you’ve got to be able to have results that are consistent across different strains of mouse, or even species of mammal; if it’s all wiped out by natural variation between organisms, there’s no way you’re getting signal usable for designing human treatments.

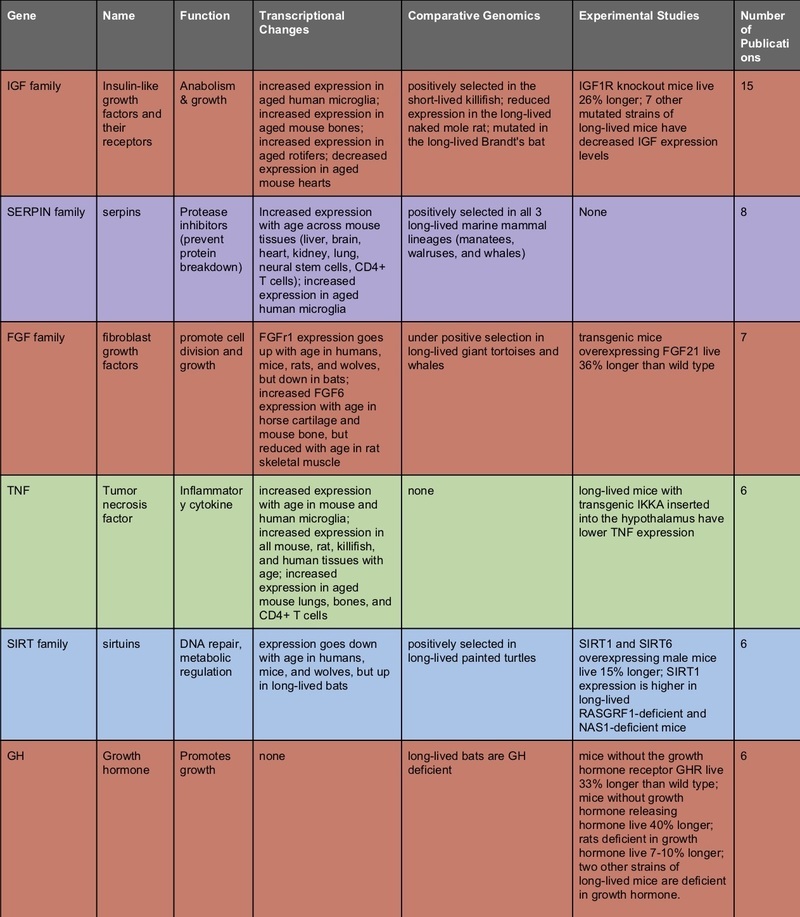

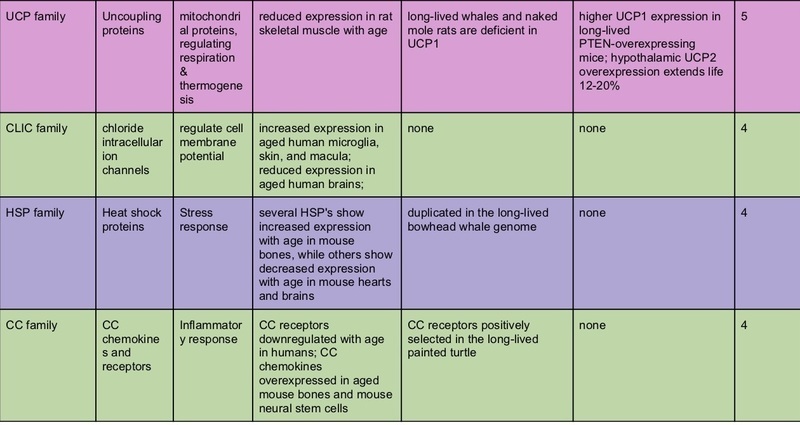

So I did a very, very crude type of meta-analysis; I looked at all the studies I could, out of these three types (transcriptomics and proteomics of aging; comparative genomics of aging in long-lived species; and interventional studies of genetic modifications; all restricted to studies on vertebrates) and ranked genes (or gene families) by the number of papers in which the gene popped out as significant.

There are a couple of potential flaws in my methodology.

First of all, I used Google Scholar to search, and stopped when the relevant search terms stopped returning studies of the relevant type. There may well have been studies this search method missed; it’s just much more time-efficient than using PubMed searches (which reliably produce far less relevant results, but it’s easier to document exactly how many papers matched search terms, which is why they’re the standard method in formal literature reviews.)

Second of all, I didn’t use a consistent cutoff in picking out which genes were significant. (In a study that tests all 20,000 or so human genes for differential expression, “statistically significant” is a very low bar.) I generally noted down the handful of genes that had the highest fold change and lowest p-value, not literally all the ones that met a significance threshold.

Thirdly, some studies, of course, like lifespan studies of a genetic modification, aren’t unbiased screens of all genes; genes that have gained more scientific interest are likely to be studied more often, so in part this list of “top genes” reflects the biases of the research literature.

And, finally, since we’re comparing different types of studies, we’re not making apples-to-apples comparisons. You don’t expect the genes differentially expressed with age to be exactly the same as the genes which are modified in long-lived organisms or the same as those which alter lifespan when experimentally mutated. If a gene shows up in all three types of studies I think that’s some sort of evidence that it’s “more likely to really be involved” in aging, but not in the same straightforward sense that it’s true that a study is more credible when it replicates exactly.

However, I think it’s worth doing something in this vein, as a way of helping orient ourselves in a growing field. As more and more papers come out claiming that they’ve found genes “associated” with aging, we want to be able to be familiar with what the most common ones that keep showing up are. Just as with genome-wide association studies for genetic predictors of disease, one correlation showing up in a study doesn’t mean we’ve found the “gene for” anything. I think of the aggregation process as a learning experience, for getting a sense of what the field as a whole looks like.

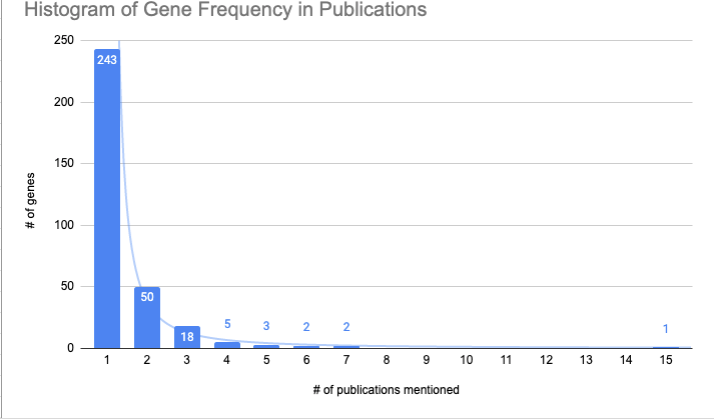

Here’s a histogram of the frequency of the distribution of the genes.

The majority of genes only appeared in one paper; most genes that were significantly related to age or lifespan in one paper did not show up in any others.

Discussion

The top-scoring gene families suggest some conclusions.

-

It’s probably worth doing interventional genetic modifications on mammals for genes that show a lot of correlational evidence of being involved in aging. Inhibiting the expression of serpins, heat shock proteins, or chemokines in mice might show a delay in some aging phenotypes.

-

Some of these genes make sense in light of the “hallmarks of aging” – serpins and heat shock proteins are associated with proteostasis and the elimination of misfolded proteins; IGF, GH, and FGF’s are involved in nutrient sensing and growth; UCP is a key mitochondrial function; TNF and the chemokines are inflammatory signals. It would make sense that dysregulation of these functions plays a causal role in age-related disease.

-

We need much larger sample sizes on longitudinal transcriptomics studies. The typical studies I found, mouse or human, had fewer than ten experimental subjects per age group. As you might expect, this yielded inconsistent results. Between-individual diversity can be a confounding factor that makes it harder to reliably identify age-related changes.

Interestingly, [22] clusters gene transcripts in human T cells according to their aging-related dynamics, and finds three kinds of genes:

1. genes that follow a "U-shaped" curve, declining in expression level until about age 60 and then rising again; these include growth-and-proliferation-associated signals

2. genes that follow an inverted-U curve, rising in expression level until about age 70 and then declining; these are mostly cancer-related genes as well as the mTOR and Jak-STAT pathways

3. genes that start out high in expression level and start to decline at age 80; these are mostly mitochondrial and neurological. I find this very interesting as a categorization and wonder if it holds up for more cell and tissue types.

From a therapeutic perspective, if this pattern generalizes, I could imagine we might want to enhance production or activity of proteins in the third cluster, inhibit the production or activity of compounds in the second cluster, and be cautious about the tradeoffs in the first cluster, since both straightforwardly inhibiting and accelerating nonspecific growth signals can have serious side effects.

It’s hard to tell, for now. But in order to replicate this result you’d also need more studies to use multiple time periods, instead of just taking old and young samples; once again, increasing the scale of longitudinal transcriptomic studies would be very valuable.

References 1. Bodyak, Natalya, et al. “Gene expression profiling of the aging mouse cardiac myocytes.” Nucleic acids research 30.17 (2002): 3788-3794. 2. Park, Sang‐Kyu, et al. “Gene expression profiling of aging in multiple mouse strains: identification of aging biomarkers and impact of dietary antioxidants.” Aging cell 8.4 (2009): 484-495.

3. Yoshida, Shigeo, et al. “Microarray analysis of gene expression in the aging human retina.” Investigative ophthalmology & visual science 43.8 (2002): 2554-2560.

4.Zhou, Jing, et al. “Integrated study on comparative transcriptome and skeletal muscle function in aged rats.” Mechanisms of ageing and development 169 (2018): 32-

5. Dobson Jr, James G., et al. “Molecular mechanisms of reduced β-adrenergic signaling in the aged heart as revealed by genomic profiling.” Physiological genomics 15.2 (2003): 142-147.

6. Yang, S., et al. “Comparative proteomic analysis of brains of naturally aging mice.” Neuroscience 154.3 (2008): 1107-1120.

7. Glaab, Enrico, and Reinhard Schneider. “Comparative pathway and network analysis of brain transcriptome changes during adult aging and in Parkinson’s disease.” Neurobiology of disease 74 (2015): 1-13.

8.Huang, Zixia, et al. “Longitudinal comparative transcriptomics reveals unique mechanisms underlying extended healthspan in bats.” Nature ecology & evolution (2019): 1.

9. Welle, Stephen, et al. “Gene expression profile of aging in human muscle.” Physiological genomics 14.2 (2003): 149-159.

10. Heras, Joseph, and Andres Aguilar. “Comparative Transcriptomics Reveals Patterns of Adaptive Evolution Associated with Depth and Age Within Marine Rockfishes (Sebastes).” Journal of Heredity 110.3 (2019): 340-350.

11. Ximerakis, Methodios, et al. “Single-cell transcriptomic profiling of the aging mouse brain.” Nature neuroscience 22.10 (2019): 1696-1708

12. Angelidis, Ilias, et al. “An atlas of the aging lung mapped by single cell transcriptomics and deep tissue proteomics.” Nature communications 10.1 (2019): 963.

- Benayoun, Bérénice A., et al. “Remodeling of epigenome and transcriptome landscapes with aging in mice reveals widespread induction of inflammatory responses.” Genome research 29.4 (2019): 697-709.

14. Taylor, Jackson, et al. “Transcriptomic profiles of aging in naïve and memory CD4+ cells from mice.” Immunity & Ageing 14.1 (2017): 15.

15. Shi, Zhanping, et al. “Single-cell transcriptomics reveals gene signatures and alterations associated with aging in distinct neural stem/progenitor cell subpopulations.” Protein & cell 9.4 (2018): 351-364

16. Kuehne, Andreas, et al. “An integrative metabolomics and transcriptomics study to identify metabolic alterations in aged skin of humans in vivo.” BMC genomics 18.1 (2017): 169.

17. Peffers, Mandy Jayne, Xuan Liu, and Peter David Clegg. “Transcriptomic signatures in cartilage ageing.” Arthritis research & therapy 15.4 (2013): R98.

18. Yu, Ying, et al. “A rat RNA-Seq transcriptomic BodyMap across 11 organs and 4 developmental stages.” Nature communications 5 (2014): 3230

19. Galatro, Thais F., et al. “Transcriptomic analysis of purified human cortical microglia reveals age-associated changes.” Nature neuroscience 20.8 (2017): 1162.

20. Galea, Gabriel L., et al. “Old age and the associated impairment of bones’ adaptation to loading are associated with transcriptomic changes in cellular metabolism, cell-matrix interactions and the cell cycle.” Gene 599 (2017): 36-52.

21. Marttila, Saara, et al. “Transcriptional analysis reveals gender-specific changes in the aging of the human immune system.” PloS one 8.6 (2013): e66229

22. Remondini, Daniel, et al. “Complex patterns of gene expression in human T cells during in vivo aging.” Molecular bioSystems 6.10 (2010): 1983-1992.

23. Gao, Lin, et al. “Age-mediated transcriptomic changes in adult mouse substantia nigra.” PloS one 8.4 (2013): e62456.

24. Cai, Hui, et al. “Effects of aging and anatomic location on gene expression in human retina.” Frontiers neuroscience 4 (2012): 8.

25. Jonker, Martijs J., et al. “Life spanning murine gene expression profiles in relation to chronological and pathological aging in multiple organs. Aging cell__ 12.5 (2013): 901-909.

26. Lewis, Kaitlyn N., et al. “Unraveling the message: insights into comparative genomics of the naked mole-rat.” Mammalian Genome 27.7-8 (2016): 259-278.

27. Keane, Michael, et al. “Insights into the evolution of longevity from the bowhead whale genome.” Cell reports 10.1 (2015): 112-122.

28. Seim, Inge, et al. “Genome analysis reveals insights into physiology and longevity of the Brandt’s bat Myotis brandtii.” Nature communications 4 (2013): 2212.

29. Quesada, Víctor, et al. “Giant tortoise genomes provide insights into longevity and age-related disease.” Nature ecology & evolution 3.1 (2019): 87.

30. Abegglen, Lisa M., et al. “Potential mechanisms for cancer resistance in elephants and comparative cellular response to DNA damage in humans.” Jama 314.17 (2015): 1850-1860.

- Seabury, Christopher M., et al. “A multi-platform draft de novo genome assembly and comparative analysis for the scarlet macaw (Ara macao).” PLOS one 8.5 (2013): e6

32. Foote, Andrew D., et al. “Convergent evolution of the genomes of marine mammals.” Nature genetics 47.3 (2015): 272.

33. Shaffer, H. Bradley, et al. “The western painted turtle genome, a model for the evolution of extreme physiological adaptations in a slowly evolving lineage.” Genome biology 14.3 (2013): R28.

34. Wirthlin, Morgan, et al. “Parrot genomes and the evolution of heightened longevity and cognition.” Current Biology 28.24 (2018): 4001-4008.

35. Wirthlin, Morgan, et al. “Parrot genomes and the evolution of heightened longevity and cognition.” Current Biology 28.24 (2018): 4001-4008.

36. Ma, Siming, and Vadim N. Gladyshev. “Molecular signatures of longevity: insights from cross-species comparative studies.” Seminars in cell & developmental biology. Vol. 70. Academic Press, 2017.

37. Fushan, Alexey A., et al. “Gene expression defines natural changes in mammalian lifespan.” Aging cell 14.3 (2015): 352-365.

38. Pickering, Andrew M., Marcus Lehr, and Richard A. Miller. “Lifespan of mice and primates correlates with immunoproteasome expression.” The Journal of clinical investigation 125.5 (2015): 2059-2068.

39. Pyo, Jong-Ok, et al. “Overexpression of ATG5 in mice activates autophagy and extends lifespan.” Nature communications 4 (2013): 2300.

40. Zhang, Yuan, et al. “The starvation hormone, fibroblast growth factor-21, extends lifespan in mice.” elife 1 (2012): e00065.

41. Conover, Cheryl A., and Laurie K. Bale. “Loss of pregnancy‐associated plasma protein A extends lifespan in mice.” Aging cell 6.5 (2007): 727-729.

42. Sun, Liou Y., et al. “Growth hormone-releasing hormone disruption extends lifespan and regulates response to caloric restriction in mice.” Elife 2 (2013): e01098.

43. Baker, Darren J., et al. “Increased expression of BubR1 protects against aneuploidy and cancer and extends healthy lifespan.” Nature cell biology 15.1 (2013): 96.

44. Selman, Colin, Linda Partridge, and Dominic J. Withers. “Replication of extended lifespan phenotype in mice with deletion of insulin receptor substrate 1.” PloS one 6.1 (2011): e16144.

45. Kanfi, Yariv, et al. “The SIRTuin SIRT6 regulates lifespan in male mice.” Nature 483.7388 (2012): 218.

46. Wu, Chia-Yu, et al. “A persistent level of Cisd2 extends healthy lifespan and delays aging in mice.” Human molecular genetics 21.18 (2012): 3956-3968.

47. Wu, Chia-Yu, et al. “A persistent level of Cisd2 extends healthy lifespan and delays aging in mice.” Human molecular genetics 21.18 (2012): 3956-3968.

48. Flurkey, Kevin, et al. “Lifespan extension and delayed immune and collagen aging in mutant mice with defects in growth hormone production.” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 98.12 (2001): 6736-6741.

49. Harper, James M., J. Erby Wilkinson, and Richard A. Miller. “Macrophage migration inhibitory factor-knockout mice are long lived and respond to caloric restriction.” The FASEB Journal 24.7 (2010): 2436-2442

50. Streeper, Ryan S., et al. “Deficiency of the lipid synthesis enzyme, DGAT1, extends longevity in mice.” Aging (Albany NY) 4.1 (2012): 13.

51. Müller, Christine, et al. “Reduced expression of C/EBPβ-LIP extends health and lifespan in mice.” Elife 7 (2018): e34985

52. de Jesus, Bruno Bernardes, et al. “Telomerase gene therapy in adult and old mice delays aging and increases longevity without increasing cancer.” EMBO molecular medicine 4.8 (2012): 691-704.

53. Canaan, Allon, et al. “Extended lifespan and reduced adiposity in mice lacking the FAT10 gene.” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 111.14 (2014): 5313-5318.

54. Al-Regaiey, Khalid A., et al. “Long-lived growth hormone receptor knockout mice: interaction of reduced insulin-like growth factor i/insulin signaling and caloric restriction.” Endocrinology 146.2 (2005): 851-860.

55. Holzenberger, Martin, et al. “IGF-1 receptor regulates lifespan and resistance to oxidative stress in mice.” Nature 421.6919 (2003): 182.

56. Schriner, Samuel E., and Nancy J. Linford. “Extension of mouse lifespan by overexpression of catalase.” Age 28.2 (2006): 209-218.

57. Schriner, Samuel E., and Nancy J. Linford. “Extension of mouse lifespan by overexpression of [[catalase]].” Age 28.2 (2006): 209-218.

58. Satoh, Akiko, et al. “SIRT1 extends life span and delays aging in mice through the regulation of Nk2 homeobox 1 in the DMH and LH.” Cell metabolism 18.3 (2013): 416-430.

59. Kurosu, Hiroshi, et al. “Suppression of aging in mice by the hormone Klotho.” Science 309.5742 (2005): 1829-1833.

60. Shimokawa, Isao, et al. “Life span extension by reduction in growth hormone-insulin-like growth factor-1 axis in a transgenic rat model.” The American journal of pathology 160.6 (2002): 2259-2265.

61. Zhang, Guo, et al. “Hypothalamic programming of systemic ageing involving IKK-β, NF-κB and GnRH.” Nature 497.7448 (2013): 211

62. Wu, J. Julie, et al. “Increased mammalian lifespan and a segmental and tissue-specific slowing of aging after genetic reduction of mTOR expression.” Cell reports 4.5 (2013): 913-920.

63. Selman, Colin, et al. “Ribosomal protein S6 kinase 1 signaling regulates mammalian life span.” Science 326.5949 (2009): 140-144

64. Ikeno, Yuji, et al. “Delayed occurrence of fatal neoplastic diseases in Ames dwarf mice: correlation to extended longevity.” The Journals of Gerontology Series A: Biological Sciences and Medical Sciences 58.4 (2003): B291-B296.

65. Matheu, Ander, et al. “Delayed ageing through damage protection by the Arf/p53 pathway.” Nature 448.7151 (2007): 375.

66. Ortega-Molina, Ana, et al. “Pten positively regulates brown adipose function, energy expenditure, and longevity.” Cell metabolism 15.3 (2012): 382-3

67. Hofmann, Jeffrey W., et al. “Reduced expression of MYC increases longevity and enhances healthspan.” Cell 160.3 (2015): 477-488.

68. Riera, Céline E., et al. “TRPV1 pain receptors regulate longevity and metabolism by neuropeptide signaling.” Cell 157.5 (2014): 1023-1036

69. Conti, Bruno, et al. “Transgenic mice with a reduced core body temperature have an increased life span.” Science 314.5800 (2006): 825-828.

70. Nóbrega-Pereira, Sandrina, et al. “G6PD protects from oxidative damage and improves healthspan in mice.” Nature communications 7 (2016): 10894.

71. Dell’Agnello, Carlotta, et al. “Increased longevity and refractoriness to Ca2+-dependent neurodegeneration in Surf1 knockout mice.” Human molecular genetics 16.4 (2007): 431-444.

72. Miskin, Ruth, and Tamar Masos. “Transgenic mice overexpressing urokinase-type plasminogen activator in the brain exhibit reduced food consumption, body weight and size, and increased longevity.” The Journals of Gerontology Series A: Biological Sciences and Medical Sciences 52.2 (1997): B118-B124.

73. Miskin, Ruth, and Tamar Masos. “Transgenic mice overexpressing urokinase-type plasminogen activator in the brain exhibit reduced food consumption, body weight and size, and increased longevity.” The Journals of Gerontology Series A: Biological Sciences and Medical Sciences 52.2 (1997): B118-B124.

74. Fernández, Álvaro F., et al. “Disruption of the beclin 1–BCL2 autophagy regulatory complex promotes longevity in mice.” Nature 558.7708 (2018): 136.

75. Vatner, Stephen F., et al. “Adenylyl cyclase type 5 disruption prolongs longevity and protects the heart against stress.” Circulation Journal 73.2 (2009): 195-200.

76.Schriner, Samuel E., et al. “Extension of murine life span by overexpression of catalase targeted to mitochondria.” science 308.5730 (2005): 1909-1911.

77. Liu, Xingxing, et al. “Evolutionary conservation of the clk-1-dependent mechanism of longevity: loss of mCLK1 increases cellular fitness and lifespan in mice.” Genes & development 19.20 (2005): 2424-2434.

- Blüher, Matthias, Barbara B. Kahn, and C. Ronald Kahn. “Extended longevity in mice lacking the insulin receptor in adipose tissue.” Science 299.5606 (2003): 572-574.

79. Borrás, Consuelo, et al. “RASGrf1 deficiency delays aging in mice.” Aging (Albany NY) 3.3 (2011): 262.

80. Matheu, Ander, et al. “Anti‐aging activity of the Ink4/Arf locus.” Aging cell 8.2 (2009): 152-161.

81. Markovich, Daniel, Mei-Chun Ku, and Dzaidenny Muslim. “Increased lifespan in hyposulfatemic NaS1 null mice.” Experimental gerontology 46.10 (2011): 833-835.

82. Redmann Jr, Stephen M., and George Argyropoulos. “AgRP-deficiency could lead to increased lifespan.” Biochemical and biophysical research communications 351.4 (2006): 860-864.

83. De Luca, Gabriele, et al. “Prolonged lifespan with enhanced exploratory behavior in mice overexpressing the oxidized nucleoside triphosphatase hMTH1.” Aging cell 12.4 (2013): 695-705.

84. Andersen, J. B., et al. “Role of 2-5A-dependent RNase-L in senescence and longevity.” Oncogene 26.21 (2007): 3081.