Melatonin's Effects on Skin and Hair

Melatonin and General Aging

Melatonin, a hormone primarily secreted by the pineal gland in the brain, is also produced in skin and hair cells. Melatonin is more than just the “sleep hormone” – it regulates the circadian rhythm, which affects many metabolic and endocrine processes.

Melatonin, and the circadian rhythm more generally, plays a role in staving off aging. Melatonin levels decline as we age, and correspondingly circadian rhythms become less regular.[1][2][3] Mice with mutations damaging their circadian rhythm have accelerated-aging syndromes, with obesity, diabetes, muscle loss, and shortened lifespans.[4][5][6] Supplementing melatonin in rodents (or administering extracts from the pineal gland[7], or grafts from fetal pineal glands[8]) has been found to extend lifespan[9][10], prolong fertility[11], reduce cancer incidence[12], reduce obesity and insulin resistance[13], and improve neurological recovery from brain injury.[14] Melatonin and compounds that act along the same pathway have potential as aging-preventative drugs.

Melatonin administration also improves skin resistance to damage (such as from UV rays) and increases hair growth.

Melatonin and Skin

In both in-vitro skin culture experiments and human studies, administering melatonin prior to exposure to UV radiation increases cell survival and reduces oxidative damage.[15] Topical melatonin applied to skin 15 minutes prior to exposure to UV radiation completely prevented skin redness (erythema) in a small randomized double-blind study of human subjects.[16][17][18]

Melatonin and Hair: Animal and Human Studies

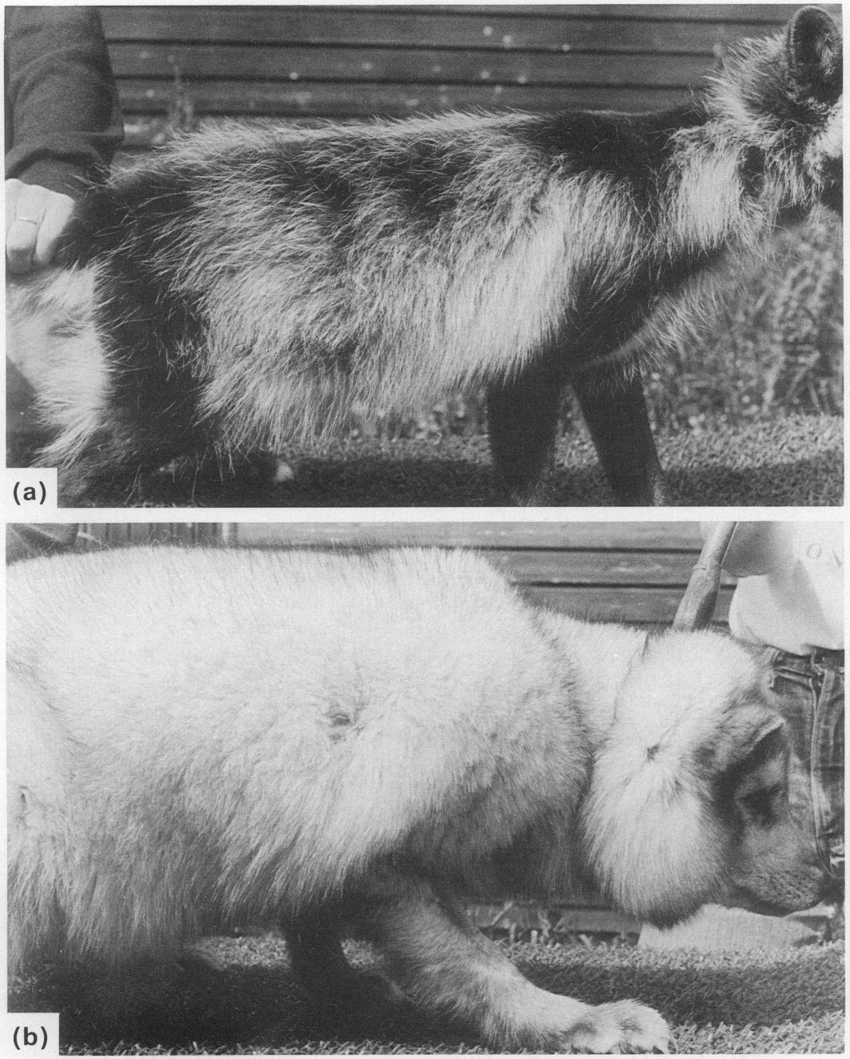

Melatonin also affects hair growth, as the hair growth cycle in mammals is under circadian control. As with other circadian cycles, the hair growth cycle becomes dysregulated and lower in amplitude with age. Mice whose circadian rhythms are damaged (via removal of the pineal gland or knockout of a circadian clock gene) show impaired hair growth as part of an accelerated aging syndrome.[17][18] When pinealectomized rats are given injections of melatonin, their hair growth recovers to that of healthy rats.[19] Melatonin administration has been found to increase hair growth in a variety of mammals: weasels[20], ewes [21], dogs[22], minks[23], goats[24], rabbits[25], and raccoon dogs[26], administered either orally or via subcutaneous implants. There’s a good evolutionary rationale for this effect: melatonin is the hormone that signals the onset of darkness, which triggers many mammals to grow thick winter coats as days grow shorter. In animals which grow white coats in winter and brown coats in summer, experimenters can trigger the growth of the white winter coat by administering melatonin.

There’s even evidence that topical melatonin can reverse hair loss in humans. In a randomized double-blind study of 40 women with hair loss, melatonin solution applied to the scalp increased hair growth significantly relative to placebo.[27] In an open-label, uncontrolled study of topical melatonin involving 1891 male and female patients with androgenic alopecia, at 3 months 61% of patients had no hair loss, compared to 12.2% at the start; 22% had new hair growth at 3 months compared to 4% at baseline. The incidence of seborrheic dermatitis also declined, from 34.5% at baseline to 9.9% at 3 months.[28]

Melatonin Precursors and Metabolites

While melatonin is a prescription-only drug in Europe, its immediate precursor n-acetylserotonin and its immediate metabolite 6-hydroxymelatonin still appear to be regulated as research chemicals.

N-acetylserotonin, like serotonin, also prevents age-related hair graying and hair loss in mice, as well as extending lifespan 20%.[29] N-acetylserotonin, like melatonin, is neuroprotective in rodents, where it improves cognitive performance.[30][31][32] Additionally, in vitro, n-acetylserotonin is an even better antioxidant than melatonin.[33] N-acetylserotonin has not yet been tested for safety in humans, but, given that it is a natural metabolite produced by the body and has been chronically administered to animals without adverse effects, the prospects for its safety are promising.

6-hydroxymelatonin, the main metabolite of melatonin, also protects against oxidative stress, in various in vivo and in vitro settings (where oxidative damage is induced by UV radiation, iron, quinolinic acid, or potassium cyanide).[34] Like N-acetylserotonin, it has not been tested for safety in humans, but because it’s a natural metabolite and has been administered safely to animals, it seems likely to prove safe in humans.

N-acetylserotonin has a short half-life in the blood and 6-hydroxymelatonin is not water soluble, which make them less favorable for oral administration; however these problems may not be relevant for topical application.

Experimental Design

In collaboration with both US and European contract research organizations (CROs) we will be testing the efficacy and safety of melatonin, n-acetylserotonin, and 6-hydroxymelatonin, first in vitro and then on human subjects.

In vitro, we will test the sensitization and toxicity effects on skin cell cultures, as well as the efficacy of these compounds in 3d skin tissue samples (a more realistic microenvironment than immortalized cell cultures) at improving regeneration after UV damage. This includes observation of histological changes, cell survival, reactive oxygen species, inflammatory cytokines, and mRNA expression of markers of cellular senescence such as p16.

In human trials, we will test any or all of these compounds (depending on their in-vitro safety) for their potential for phototoxicity and sensitization, as well as their effects on hair density and skin thickness.

References

[1]Waldhauser, F., J. Ková, and E. Reiter. “Age-related changes in melatonin levels in humans and its potential consequences for sleep disorders.” Experimental gerontology 33.7-8 (1998): 759-772.

[2]REITER, RUSSEL J., et al. “Age-associated reduction in nocturnal pineal melatonin levels in female rats.” Endocrinology 109.4 (1981): 1295-1297.

[3]Mattis, Joanna, and Amita Sehgal. “Circadian rhythms, sleep, and disorders of aging.” Trends in Endocrinology & Metabolism 27.4 (2016): 192-203.

[4]Marcheva, Biliana, et al. “Disruption of the clock components CLOCK and BMAL1 leads to hypoinsulinaemia and diabetes.” Nature 466.7306 (2010): 627.

[5]Kondratov, Roman V., et al. “Early aging and age-related pathologies in mice deficient in BMAL1, the core component of the circadian clock.” Genes & development 20.14 (2006): 1868-1873.

[6]Turek, Fred W., et al. “Obesity and metabolic syndrome in circadian Clock mutant mice.” Science 308.5724 (2005): 1043-1045.

[7]Dilman, V. M., et al. “Increase in lifespan of rats following polypeptide pineal extract treatment.” Experimentelle Pathologie 17.9 (1979): 539-545.

[8]Hurd, Mark W., and Martin R. Ralph. “The significance of circadian organization for longevity in the golden hamster.” Journal of biological rhythms 13.5 (1998): 430-436.

[9]Oxenkrug, G., P. Requintina, and S. Bachurin. “Antioxidant and antiaging activity of N‐acetylserotonin and melatonin in the in vivo models.” Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences 939.1 (2001): 190-199.

[10]Anisimov, Vladimir N., et al. “Melatonin increases both life span and tumor incidence in female CBA mice.” The Journals of Gerontology Series A: Biological Sciences and Medical Sciences 56.7 (2001): B311-B323.

[11]Meredith, S., et al. “Long-term supplementation with melatonin delays reproductive senescence in rats, without an effect on number of primordial follicles☆.” Experimental gerontology 35.3 (2000): 343-352.

[12]El-Domeiri, Ali AH, and Tapas K. Das Gupta. “Reversal by melatonin of the effect of pinealectomy on tumor growth.” Cancer research 33.11 (1973): 2830-2833.

[13]Wolden-Hanson, T., et al. “Daily melatonin administration to middle-aged male rats suppresses body weight, intraabdominal adiposity, and plasma leptin and insulin independent of food intake and total body fat.” _Endocrinology_141.2 (2000): 487-497.

[14]Kilic, Ertugrul, et al. “Pinealectomy aggravates and melatonin administration attenuates brain damage in focal ischemia.” Journal of Cerebral Blood Flow & Metabolism 19.5 (1999): 511-516.

[15]Kleszczynski, Konrad, and Tobias W. Fischer. “Melatonin and human skin aging.” Dermato-endocrinology 4.3 (2012): 245-252.

[16]Fischer, Tobias W., et al. “Melatonin as a major skin protectant: from free radical scavenging to DNA damage repair.” Experimental dermatology 17.9 (2008): 713-730.

[17]Geyfman, Mikhail, and Bogi Andersen. “Clock genes, hair growth and aging.” Aging (Albany NY) 2.3 (2010): 122

[18]Kondratov, Roman V., et al. “Early aging and age-related pathologies in mice deficient in BMAL1, the core componentof the circadian clock.” Genes & development 20.14 (2006): 1868-1873.

[19]Eşrefoğlu, Mukaddes, et al. “Potent therapeutic effect of melatonin on aging skin in pinealectomized rats.” Journal of pineal research 39.3 (2005): 231-237.

[20]Rust, Charles C., and Roland K. Meyer. “Hair color, molt, and testis size in male, short-tailed weasels treated with melatonin.” Science 165.3896 (1969): 921-922.

[21]Santiago-Moreno, J., et al. “Effect of constant-release melatonin implants and prolonged exposure to a long day photoperiod on prolactin secretion and hair growth in mouflon (Ovis gmelini musimon).” Domestic animal endocrinology 26.4 (2004): 303-314.

[22]FRANK, LINDA A., KEITH A. HNILICA, and JACK W. OLIVER. “Adrenal steroid hormone concentrations in dogs with hair cycle arrest (Alopecia X) before and during treatment with melatonin and mitotane.” Veterinary dermatology 15.5 (2004): 278-284.

[23]Allain, D., and J. Rougeot. “Induction of autumn moult in mink (Mustela vison Peale and Beauvois) with melatonin.” Reproduction Nutrition Développement 20.1A (1980): 197-201.

[24]Dicks, P., A. J. F. Russel, and G. A. Lincoln. “The effect of melatonin implants administered from December until April, on plasma prolactin, triiodothyronine and thyroxine concentrations and on the timing of the spring moult in cashmere goats.” Animal Science 60.2 (1995): 239-247.

[25]Lanszki, József, et al. “The effects of melatonin treatment on wool production and hair follicle cycle in angora rabbits.” Animal Research 50.1 (2001): 79-89.

[26]Xiao, Yongjun, et al. “Effects of melatonin implants on winter fur growth and testicular recrudescence in adult male raccoon dogs (Nyctereutes procyonoides).” _Journal of pineal research_20.3 (1996): 148-156.

[27]Fischer, T. W., et al. “Melatonin increases anagen hair rate in women with androgenetic alopecia or diffuse alopecia: results of a pilot randomized controlled trial.” British Journal of Dermatology 150.2 (2004): 341-345.

[28]Fischer, Tobias W., et al. “Topical melatonin for treatment of androgenetic alopecia.” International journal of trichology 4.4 (2012): 236.

[29]Oxenkrug, G., P. Requintina, and S. Bachurin. “Antioxidant and antiaging activity of N‐acetylserotonin and melatonin in the in vivo models.” Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences 939.1 (2001): 190-199.

[30]Bachurin, S., et al. “N‐Acetylserotonin, Melatonin and Their Derivatives Improve Cognition and Protect against β‐Amyloid‐Induced Neurotoxicity.” Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences 890.1 (1999): 155-166.

[31]Sompol, Pradoldej, et al. “N-acetylserotonin promotes hippocampal neuroprogenitor cell proliferation in sleep-deprived mice.” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 108.21 (2011): 8844-8849.

[32]Iuvone, P. Michael, et al. “N-acetylserotonin: circadian activation of the BDNF receptor and neuroprotection in the retina and brain.” Retinal Degenerative Diseases. Springer, New York, NY, 2014. 765-771.

[33]Wölfler, Albert, et al. “N‐acetylserotonin is a better extra‐and intracellular antioxidant than melatonin.” FEBS letters 449.2-3 (1999): 206-210.

[34]Álvarez-Diduk, Ruslán, et al. “N-Acetylserotonin and 6-hydroxymelatonin against oxidative stress: Implications for the overall protection exerted by melatonin.” The Journal of Physical Chemistry B 119.27 (2015): 8535-8543.