High-Throughput Invertebrate Drug Screens

Biogerontologists have found many different drugs that appear to extend lifespan in various animals – despite having tested relatively few drugs to date. A broad screening effort for aging-modifying drugs could discover many more, some of which might translate to humans, and might also help us better understand the mechanisms of aging.

How can you efficiently test lots of drugs for their effect on lifespan? You need a short-lived model organism and a _low cost per experiment _enabled by automation. Fortunately, we’ve begun to see good results from that approach, though it hasn’t yet been deployed at scale and still has a lot of potential for more growth and improvement, which we’re hoping to do at LRI.

Nematode Worms as Model Organisms

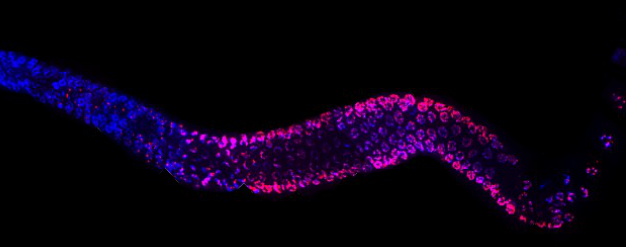

The obvious choice for a model organism is C. elegans, a species of nematode worm which is well-studied in aging biology, fully genetically sequenced, and provided the first known examples of artificial life extension.

_C. elegans _has a lifespan of only 2-3 weeks. It can easily be grown on agar medium with _E. coli _bacteria for food, and pipetted onto petri dishes or well plates containing medium, along with any drugs being tested; in other words, it’s a good candidate for use with robotic laboratory automation tools, which reduce the labor costs and improve the accuracy of large-scale experiments.

_C. elegans _is also transparent and easy to observe with low-magnification microscopes or even high-resolution cameras without magnification. This means that we can also automate the _observation _process of detecting worm survival time and even some other phenotypes, like activity (which declines as worms age), pigmentation (which changes as worms age), and pharyngeal pumping (which is how worms eat, and can be used to understand whether dietary restriction is occurring).

The CITP, or Caenorhabditis Interventions Testing Program, a multicenter collaboration funded by the NIA, has done valuable work in examining how variations in worm strain, cohort, experimental conditions, and laboratory site affect the lifespan of worms exposed to different well-known drugs. They found[1] quite significant variation in drug effectiveness between worm strains for several dietary restriction mimetics (suggesting that these will not generalize well beyond C. elegans) and variation between laboratory sites (suggesting that, even with carefully written protocols, standardizing and replicating experiments is difficult.) These insights will be essential to keep in mind in any systematic nematode drug screen for longevity.

Some other short-lived invertebrates, like the water flea, Daphnia, are also potential candidates; they’re less well-studied, but they ingest drugs dissolved in their water more easily than nematodes do, so accurate dosing is more possible. The rest of this essay will focus on nematodes because that’s where the most prior work exists and it’s easiest to assess the results, but that shouldn’t be taken to imply that we’ve ruled out studying other invertebrate models.

Automated Worm Lifespan Assays

Automated lifespan assays for _C. elegans _have recently been developed in several labs (Lifespan Machine[2], WormFarm[3], WorMotel[4], WormBot[5]).

These setups range from petri dishes on flatbed scanners (Lifespan Machine), microfluidic chips for use with light or fluorescence microscopes (WormFarm, WorMotel), and a robotically mounted camera suitable for arrays of standard well plates (WormBot.)

This last, potentially with modifications to ensure reliability at scale (like a robotic arm to move plates around a rigidly mounted camera instead of vice versa, and integration of the camera + plate setup with robotic fluid handling machines) seems the most compatible with the very large number of well plates necessary for screening thousands of different drugs in parallel.

Special-purpose programming languages for laboratory automation also exist, which allow creating protocols programatically and algorithmically optimizing fluid handling to maximize throughput and accuracy. Using these software tools might well reduce cost per experiment (in time and reagents) and improve replicability relative to the already high CITP standard.

Use of Machine Learning in Longevity Drug Screens

Existing software for detecting worm survival is primitive, using only pixel counting, and in some cases requiring manual tagging of worms. This is still adequate for identifying if worms are alive or dead (automatic scoring is a close match to manual scoring) but is still labor intensive and doesn’t make full use of the rich information available in high-resolution video of worms.

Current machine learning algorithms are capable of automatically tracking objects[6] in video; instead of counting how many _live worms there are in a given well at a given time, we can also track individual worms over time, without the need for manual tagging. Moreover, we can regress video data to produce a prediction of worm age based on visual features (including behavioral features) of worms – this would allow us to produce a score of _how young a worm looks. Such a score would allow us to rate drugs by their effect on healthspan as well as lifespan. We expect that this is possible because visual inspection by biologists _does _easily distinguish between young, healthy worms and old, sick worms.

Automated analysis of video/image data could reduce the labor costs of observation and scoring in a 6000-drug screen by at least a factor of ten, and by much more in the long run, since the cost of building and maintaining the machine learning model grows slowly relative to the number of drugs screened, while the cost of manually inspecting more worms grows linearly.

Odds of Success

Even a “brute force” search through a diverse library of drugs, without assuming any knowledge about which drugs are likely to have pro-longevity effects, will likely turn up enough new hits to be worth the investment. The few existing drug screens for longevity in worms bear this out.

In one drug screen, from the Petrascheck Lab at Scripps, for lifespan in C. elegans, out of 88,000 chemicals tested, 115 compounds statistically increased lifespan, or about 0.1%.[6] Another screen, from the Lithgow Lab at the Buck institute, found 57 replicable hits for longevity in _C. elegans _out of a drug screen of 30,000 drug-like compounds, or about 0.2%.[7]

In the Petrascheck Lab’s more targeted screen, of a standard commercially available library (the LOPAC-1280) of 1280 compounds selected for mammalian bioactivity, 60 compounds, or 5%, statistically increased lifespan in C. elegans.[6] In other words, when we restrict attention to chemicals that we know do _something _in mammals (many of which are FDA-approved drugs), quite a large fraction of them extend life in nematode worms.

(Note that neither of these screens was done with automated lifespan-assessment platforms; so far, all invertebrate drug screens for longevity have been performed manually.)

But, of course, extending life in a worm is no guarantee of extending life in other organisms. How likely is that? We have no exact measurement, but we do have the DrugAge database[8] of compounds that have been found to extend life in various species. 7% of the drugs listed as extending life in nematodes have also been found to extend life in mammals. This is, in fact, an underestimate, since the majority of drugs tested in worms were likely never tested on mammals (given the high cost and relative rarity of mammalian lifespan experiments.)

Combining these two figures, we can get a rough estimate of 0.35% probability that a compound with mammalian bioactivity, tested on nematodes, will extend life in mammals. In other words, screening 6000 new drugs in worms will yield, in expectation, 300 hits for life extension, of which we expect 21 to also extend life in mice.

Of course, in real life, we can’t do 300 separate mouse lifespan studies. What we can do is take those 300 primary hits in worms, and narrow them down to a more tractable set by doing more invertebrate studies – selecting for drugs with consistent effects across different worm strains and experimental conditions as in the CITP, selecting for drugs that also modify healthspan and other aging-related phenotypes, and running validation assays to select for drugs with biologically plausible mechanisms of action (such as altering transcription or activation of known aging-related pathways, or clearing senescent cells.) Applying these more stringent filters, we could get a “top-15” list of candidate drugs worth testing in mammals. And even if (to be quite conservative) these secondary filters don’t allow us to improve _at all _on the 7% transferability rate at baseline, we’ll _still _expect that on average at least one of these drugs will extend life in mammals.

What We’ll Need

Most importantly, we’ll need a small team of great people.

- A biogerontologist, ideally specializing in invertebrate aging, to lead the research program

- An additional junior scientist/technician, with demonstrated research interest in aging, to conduct experiments and procedures

- A roboticist or hardware engineer with experience in laboratory automation, to build the apparatus for invertebrate screening and video monitoring

- A machine learning engineer with experience with video/image data, ideally with demonstrated interest in biology, to build the software and models for scoring invertebrates on lifespan and healthspan, as well as monitoring/assessment of the automated screening platform itself.

- A generalist lab manager to handle procurement, maintenance, and other lab operations.

We’ll also need lab space, lab equipment, reagents and consumables, and materials/computational resources for building the automated screening platform.

Preliminary cost estimates for one year of operation:

| Labor (salaries, benefits, taxes, professional services) | $1,200,000 USD |

| Rent | $500,000 USD |

| Equipment and Utilities | $150,000 USD |

| Reagents (including an initial drug library of 6000 bioactive compounds) | $90,000 USD |

| Insurance | $10,000 USD |

| Total | $2,000,000 USD |

Scaling to an even larger range of compounds is likely going to be cost-effective, given that, with a mostly automated screening process, labor and rent costs will grow much more slowly than screening volume.

In the next post, I’ll cover how mammalian lifespan experiments can be designed to _also _be much more efficient in time and cost scaling with the number of drug candidates.

References

[1]Lucanic, Mark, et al. “Impact of genetic background and experimental reproducibility on identifying chemical compounds with robust longevity effects.” Nature communications 8 (2017): 14256.

[2]Stroustrup, Nicholas, et al. “The Caenorhabditis elegans lifespan machine.” Nature methods 10.7 (2013): 665.

[3]Xian, Bo, et al. “WormFarm: a quantitative control and measurement device toward automated Caenorhabditis elegans aging analysis.” Aging cell 12.3 (2013): 398-409.

[4]Churgin, Matthew A., et al. “Longitudinal imaging of Caenorhabditis elegans in a microfabricated device reveals variation in behavioral decline during aging.” Elife 6 (2017).

[6]Hu, Yuan-Ting, Jia-Bin Huang, and Alexander Schwing. “Maskrnn: Instance level video object segmentation.” Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems. 2017.

[7]Petrascheck, Michael, Xiaolan Ye, and Linda B. Buck. “An antidepressant that extends lifespan in adult Caenorhabditis elegans.” Nature 450.7169 (2007): 553.

[8]Barardo, Diogo, et al. “The DrugAge database of aging‐related drugs.” Aging cell 16.3 (2017): 594-597.