Tryptophan-Kynurenine Metabolism and Neurological Approaches to Aging Therapeutics

It’s a curious fact that the drugs which extend life the most in experiments on both mammals and nematodes are not dietary-restriction mimetics but neurologically active drugs.

Seven of the top twenty rodent lifespan extending drugs by effect size act primarily on the brain: fullerenes, epitalon, polypeptide bovine pineal extract, melatonin, ginkgo biloba extract, and selegiline.[1] Selegiline, an MAO inhibitor, is the only drug that has been reported to extend life in a large mammal (dogs.)

Unbiased drug screens measuring effect on _C. elegans_lifespan, from the Petrascheck lab at Scripps, also reveal neurologically active drugs as among the most effective.

In a screen of 88,000 small-molecule drugs, four drugs with related structures that affect serotonin metabolism in the brain (5-HT2 receptor antagonists) were found to extend lifespan in C. elegans by 20-33%: mianserin, mirtazapine, cyproheptadine, and miothepin. Mianserin + dietary restriction extends lifespan only 4% more than DR alone, suggesting its effect might be dietary restriction related; however, it does not reduce pharyngeal pumping (the nematode’s method of eating), so it does not directly cause dietary restriction.[2]

Out of a library of 1280 compounds with known or suspected mammalian targets, 57 extended life in nematodes, and 29 of these targeted the receptors of biogenic amines found in neurotransmission: adrenaline, dopamine, histamine, and serotonin_._ Ten (amoxapine, nortriptyline, clorotepine, chlorprothixine, loxapine, pergolide, thioridazine, promethazine, amperozide, mianserin) are antidepressants and/or antipsychotics. The biggest effect size was loxapine, at 43%.[3]

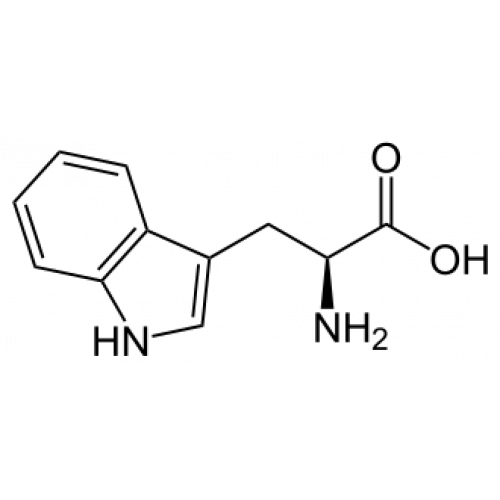

Note that many of these drugs affect serotonin (selegiline, loxapine, mianserin, etc) or melatonin (melatonin, epitalon, and polypeptide pineal extract) Serotonin is produced from the amino acid tryptophan, and melatonin is produced from serotonin; on the other hand, roughly 95% of the tryptophan in the body is instead broken down into kynurenine, which has diverse functions in cellular metabolism and is a precursor of NAD+. Increasing levels of serotonin or melatonin shift tryptophan down the serotonin-melatonin pathway and away from the kynurenine pathway.

The Neuroendocrine Hypothesis and Tryptophan-Kynurenine Metabolism

There’s a theory (promulgated by Gregory Oxenkrug of Tufts University) that shifting tryptophan metabolism towards serotonin and melatonin, and away from kynurenine, has anti-aging effects.[4] Kynurenine metabolism is associated with various age-related diseases, such as the metabolic syndrome (hypertension, obesity, dyslipidemia, diabetes type 2), as well as chronic inflammation and impaired immune defense, and some types of cancers, heart disease, and vascular dementia.

The rate-limiting enzyme in converting tryptophan to kynurenine is IDO, indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase, which is found in astrocytes, microglia, microvascular endothelial cells, and macrophages. That is, the cells active in chronic inflammation.

Kynurenine and its derivatives also stimulate synthesis of nitric oxide, which stimulates production of lots of inflammation-related nasties: COX2, prostaglandins, and leukotrienes, all found elevated in the metabolic syndrome.

Inflammation, cortisol, and sex hormones are associated with upregulating the tryptophan-to-kynurenine-to-NAD pathway, while melatonin and serotonin are associated with inhibiting it. The female sex hormones estradiol and progesterone upregulate the kynurenine-NAD pathway; so does the inflammatory cytokine IFN-gamma. Melatonin and serotonin inhibit tryptophan-kynurenine metabolism, while the sex hormones estrogen and testosterone and the stress hormone cortisol upregulate it. The pro-inflammatory cytokines IFN-gamma, IFN-alpha, and TNF-alpha also upregulate IDO (and hence kynurenine production).[4] This is all in line with the _anti-_gonadal tendency of melatonin supplementation in rodents – it reduces gonadal growth, delays the onset of fertility, and so on. Similarly, sex hormones are elevated in metabolic syndrome and certain types of cancer (prostate, breast, ovarian.)

IDO activity correlates with nasties: age, mortality, LDL, BMI, and CRP. Kynurenine/tryptophan ratio also correlates with nasties: coronary heart disease and morbid obesity.[4] Kynurenine derivative levels are elevated in type II diabetes; so is the kynurenine-to-tryptophan ratio. Kynurenine-to-tryptamine levels and IDO expression are also higher in obese subjects, and (unlike other inflammatory factors) do not normalize after weight loss.[5]

The picture Oxenkrug is painting is one in which tryptophan metabolism into kynurenine causes many of the diseases of aging, and counteracting this pathway could extend life.

The related “neuroendocrine hypothesis of aging” proposed by Oxenkrug’s advisor Vladimir Dilman (the Soviet endocrinologist who also was the first to observe that pineal extracts and antidiabetic drugs extend life in mice) argues that as the hypothalamus becomes less sensitive to negative feedback, it overproduces hormones which accelerate aging. There are several physiological facts that support this hypothesis. Neurotransmitters in the hypothalamus decline with age: norepinephrine in rhesus monkey and rat, dopamine in rat, and serotonin in rhesus monkey. In humans and rats, the hypothalamus becomes less sensitive to glucocorticoid and gonadal steroid negative feedback with age. Compared to young controls, blood hormone levels are elevated for gonadotropins in postmenopausal women, for cortisol after surgery in elderly patients, and for growth hormone after glucose loading in elderly patients.[6]

So you can imagine a picture in which the hypothalamus’ continued production of stress, sex, and growth hormones, and decline in serotonin levels, pushes tryptophan metabolism down the kynurenine pathway, which leads to chronic inflammation, obesity, and diseases of aging. In this model, fixing the brain might fix the rest of the body.

Evidence that Tryptophan-Kynurenine Metabolism is Associated with Age-Related (and other) Disease

General Aging and Mortality

In a study of 284 elderly adults, kynurenine-to-tryptophan ratios are associated with age (p=0.0001), higher levels of inflammation (as measured by IL-6 and CRP), depressive symptoms, and fatigue symptoms.[7]

Kynurenine-to-tryptophan ratios are also higher in elderly adults than in a general population of blood donors.[8]

Plasma levels of inflammatory markers (neopterin, kynurenine:tryptophan ratio, and C-reactive protein), and 3-hydroxykynurenine (a kynurenine metabolite) in humans were positively associated with all-cause mortality (p<0.001), and tryptophan (p<0.001) and xanthurenic acid (p = 0.021) were inversely associated with mortality in a longitudinal study of 7019 middle-aged and elderly subjects from Hordaland County, Norway.[9]

Old rats have increased kynurenine and IDO activity in the brain compared to young rats, though less in the liver & kidney.[10]

Depression

Interestingly enough, the so-called “serotonin hypothesis of depression” which catalyzed the development of SSRI antidepressants was originally not a claim merely that depression was a disease of low serotonin levels, but that it was about tryptophan metabolism being directed to kynurenine. “The original 1969 Lancet paper [posing the serotonin hypothesis of depression] proposed, “in depression the activity of liver tryptophan-pyrrolase is stimulated by raised blood corticosteroids levels, and metabolism of tryptophan is shunted away from serotonin production, and towards kynurenine production.””[11] So theories of depression that claim it’s driven by chronic inflammation or hypercortisolism are actually consistent with the serotonin hypothesis.

Correspondingly, we observe that kynurenine-to-tryptophan ratios are higher in patients with major depression.[12]

Neurodegenerative diseases

Kynurenine derivatives are elevated in multiple sclerosis, ALS, Huntington’s disease, Parkinson’s disease, and Alzheimer’s disease, especially the excitotoxic metabolite quinolinic acid, produced by activated microglia & macrophages.[13][8]

3-hydroxykynurenine, a kynurenine metabolite, is elevated in patients with Huntington’s disease.[14]

In an autopsy study of 13 patients with Alzheimer’s and 11 controls, kynurenate (a derivative of kynurenine) was increased significantly in the putamen and caudate nucleus of AD patients, by 192 and 177%, respectively.[15]

In a study of 34 patients with Alzheimer’s and 18 controls, the Alzheimer’s patients had significantly lower serum tryptophan and kynurenate, and significantly higher quinolinic acid (a neurotoxic metabolite of kynurenine.)[16]

In an autopsy study of subjects with and without Parkinson’s disease, the PD brains had lower dopamine and serotonin concentrations, and lower kynurenine and kyurenate levels, but higher 3-hydroxykynurenine levels.[17]

Compared to control patients, patients with ALS had significantly increased levels of CSF and serum tryptophan (p < 0.0001), kynurenine (p < 0.0001) and quinolinic acid. (p < 0.05)[18]

While the details of differences in kynurenine metabolism seem to be inconsistent between studies, alteration in kynurenine metabolism seems to be a common finding in neurodegenerative disease.

Other inflammatory disease

Irritable bowel disease patients have elevated levels of kynurenine and kynurenate. Kynurenine levels correlate with the severity of pancreatitis, and melatonin and inhibition of kynurenine-3-monooxidase are both treatments for acute pancreatitis. [19]

Extending Lifespan via Tryptophan-Kynurenine Metabolism

Inhibiting or knocking out IDO (one of the tryptophan-to-kynurenine enzymes) in mice prevents tumor growth and formation; depletion of tdo-2 in C. elegans and vermilion in Drosophila (the fruit fly gene for TDO, the other tryptophan-to-kynurenine enzyme) extends lifespan in both species and prevents models of neurodegenerative disease. Rapamycin, the famed mTOR inhibitor and life-extension drug, also inhibits TDO.[20]

Inhibitors of TDO, alpha-methyl tryptophan and 5-methyl tryptophan, increase fly mean and maximum lifespan (by 27% and 43%, and 21% and 23%, respectively.)[21]

Vermilion flies (a mutation without functional TDO) live 75% longer than wild-type![22]

Minocycline and berberine, both IDO inhibitors, extend fruit fly lifespan, p<0.0002.[23] Berberine is also a cholesterol-lowering and glucose-lowering compound[24][25], while minocycline has been investigated for neuroprotective, anti-inflammatory, antidepressant, and antipsychotic properties, and at 63% life extension, has the second-largest effect on fruit fly lifespan of any compound reported to extend life in Drosophila.

TDO knockout C. elegans live 15% longer.[26]

Finally, in an RNAi knockdown screen (at the Sutphin Lab at the University of Arizona) testing whether blocking the expression of genes differentially expressed with age in humans extends life in C. elegans, the biggest impact on longevity (>30%) is a knockdown of kynu-1, which codes for kynureninase, the enzyme that breaks down kynurenine. Kynu-1 alone delayed pathology in models of Alzheimer’s & Huntington’s. The effect still works on daf-1, hif-1, eat-2, rsks-1, and sir-2.1 mutants.[27]

In unpublished data from the Sutphin lab, HAAO-1 knockouts & knockdowns (a gene farther down the kynurenine metabolism pathway) and 3HAA supplementation also extend lifespan, by even more (40% median lifespan increase.)

Conclusions

There are a lot of competing “theories of aging”, so why should tryptophan-kynurenine metabolism rise to our attention?

Well, it shows up in multiple independent exploratory screens:

- Top lifespan-extending drugs in mammals

- Top lifespan-extending drugs in Drosophila

- Lifespan drug screens of C. elegans

- RNAi knockdown screens of C. elegans

Tryptophan-kynurenine metabolism may even be upstream of caloric restriction’s beneficial effect on lifespan, especially given that blocking kynurenine metabolism still extends life in worms that are already dietary-restricted or have altered nutrient sensing.

References

[1]Barardo, D., Thornton, D., Thoppil, H., Walsh, M., Sharifi, S., Ferreira, S., Anzic, A., Fernandes, M., Monteiro, P., Grum, T., Cordeiro, R., De-Souza, E.A., Budovsky, A., Araujo, N., Gruber, J., Petrascheck, M., Fraifeld, V.E., Zhavoronkov, A., Moskalev, A., de Magalhaes, J.P. (2017) “The DrugAge database of ageing-related drugs.” 16:594-597. Aging Cell 16(3):594-597.

[2]Petrascheck, Michael, Xiaolan Ye, and Linda B. Buck. “A high‐throughput screen for chemicals that increase the lifespan of Caenorhabditis elegans.” Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences 1170.1 (2009): 698-701.

[3]Ye, Xiaolan, et al. “A pharmacological network for lifespan extension in C aenorhabditis elegans.” Aging cell 13.2 (2014): 206-215.

[4]Oxenkrug, Gregory F. “Metabolic syndrome, age‐associated neuroendocrine disorders, and dysregulation of tryptophan—kynurenine metabolism.” Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences 1199.1 (2010): 1-14.

[5]Oxenkrug, Gregory. “Insulin resistance and dysregulation of tryptophan–kynurenine and kynurenine–nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide metabolic pathways.” _Molecular neurobiology_48.2 (2013): 294-301.

[6]Everitt, Arthur V. “The neuroendocrine system and aging.” Gerontology 26.2 (1980): 108-119.

[7]Capuron, Lucile, et al. “Chronic low-grade inflammation in elderly persons is associated with altered tryptophan and tyrosine metabolism: role in neuropsychiatric symptoms.” Biological psychiatry 70.2 (2011): 175-182.

[8]Widner, B., et al. “Tryptophan degradation and immune activation in Alzheimer’s disease.” Journal of neural transmission 107.3 (2000): 343-353.

[9]Zuo, Hui, et al. “Plasma biomarkers of inflammation, the kynurenine pathway, and risks of all-cause, cancer, and cardiovascular disease mortality: The Hordaland Health Study.” American journal of epidemiology 183.4 (2016): 249-258.

[10]Braidy, Nady, et al. “Changes in kynurenine pathway metabolism in the brain, liver and kidney of aged female Wistar rats.” The FEBS journal 278.22 (2011): 4425-4434.

[11]Oxenkrug, Gregory F. “Tryptophan–kynurenine metabolism as a common mediator of genetic and environmental impacts in major depressive disorder: the serotonin hypothesis revisited 40 years later.” The Israel journal of psychiatry and related sciences 47.1 (2010): 56.

[12]Myint, Aye-Mu, et al. “Kynurenine pathway in major depression: evidence of impaired neuroprotection.” Journal of affective disorders 98.1-2 (2007): 143-151

[13]Oxenkrug, Gregory F. “The extended life span of Drosophila melanogaster eye-color (white and vermilion) mutants with impaired formation of kynurenine.” Journal of neural transmission 117.1 (2010): 23.

[14]Pearson, S. J., and G. P. Reynolds. “Increased brain concentrations of a neurotoxin, 3-hydroxykynurenine, in Huntington’s disease.” Neuroscience letters 144.1-2 (1992): 199-201.

[15]Baran, H., K. Jellinger, and L. Deecke. “Kynurenine metabolism in Alzheimer’s disease.” Journal of neural transmission 106.2 (1999): 165-181.

[16]Gulaj, E., et al. “Kynurenine and its metabolites in Alzheimer’s disease patients.” Advances in Medical Sciences 55.2 (2010): 204-211.

[17]Ogawa, T., et al. “Kynurenine pathway abnormalities in Parkinson’s disease.” Neurology 42.9 (1992): 1702-1702.

[18]Chen, Yiquan, et al. “The kynurenine pathway and inflammation in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis.” Neurotoxicity research 18.2 (2010): 132-142.

[19]Cervenka, Igor, Leandro Z. Agudelo, and Jorge L. Ruas. “Kynurenines: tryptophan’s metabolites in exercise, inflammation, and mental health.” Science 357.6349 (2017): eaaf9794.

[20]Van der Goot, Annemieke T., and Ellen AA Nollen. “Tryptophan metabolism: entering the field of aging and age-related pathologies.” Trends in molecular medicine 19.6 (2013): 336-344.

[21]Oxenkrug, Gregory F., et al. “Extension of life span of Drosophila melanogaster by the inhibitors of tryptophan-kynurenine metabolism.” Fly 5.4 (2011): 307-309.

[22]Oxenkrug, Gregory F. “The extended life span of Drosophila melanogaster eye-color (white and vermilion) mutants with impaired formation of kynurenine.” Journal of neural transmission 117.1 (2010): 23.

[23]Oxenkrug, Gregory, et al. “Minocycline effect on life and health span of Drosophila melanogaster.” Aging and disease 3.5 (2012): 352.

[24]Kong, Weijia, et al. “Berberine is a novel cholesterol-lowering drug working through a unique mechanism distinct from statins.” Nature medicine 10.12 (2004): 1344.

[25]Yin, Jun, Huili Xing, and Jianping Ye. “Efficacy of berberine in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus.” Metabolism 57.5 (2008): 712-717.

[26]Van Der Goot, Annemieke T., et al. “Delaying aging and the aging-associated decline in protein homeostasis by inhibition of tryptophan degradation.” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (2012): 201203083.

[27]Sutphin GL, Backer G, Sheehan S, Bean S, Corban C, Liu T, Peters MJ, van Meurs JBJ, Muribito JM, Johnson AD, Korstanje R. C. elegans Orthologs of Human Genes Differentially Expressed with Age are Enriched for Determinants of Longevity. Aging Cell