Stem Cell Transplants

This is Part 4 in our series of posts on types of treatments that might extend healthy lifespan.

What are Stem Cell Transplants?

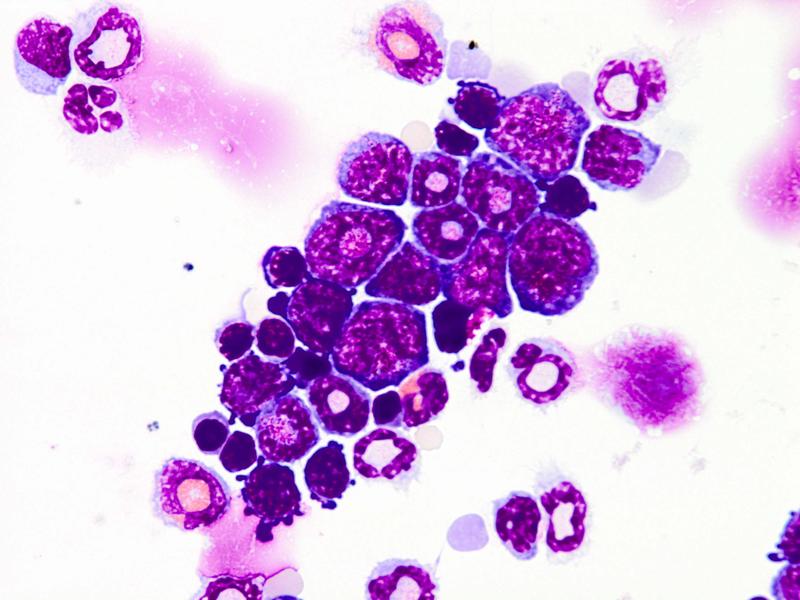

Stem cells, frequently found in bone marrow, are pluripotent cells that can develop into various cell types. The ability of stem cells to regenerate declines with age, so it might make sense that transplanting stem cells from young to old animals would improve symptoms of aging. There does seem to be preliminary evidence that stem cell transplants can extend lifespan and reduce frailty.

Transplants themselves may not be a very practical treatment for humans, given that they require immunosuppression and thus are fairly dangerous procedures, especially if given as a preventative rather than a disease treatment. But if stem cell transplants are effective, that provides a model from which to develop (potentially safer) techniques to rejuvenate old stem cells.

Bone Marrow Transplants

Mesenchymal stem cell transplants from young mice into old mice significantly increased mean lifespan, by 16.3%. Treated mice also had significantly more bone mineral density.[1]

Bone marrow transplants from young mice into aged mice increased the number of progenitor cells in bone marrow and myocardium. After artificially induced myocardial infarction (from closing the coronary artery) the mice with bone marrow transplants recovered better: increased ejection fraction, lower end-systolic and end-diastolic ventricular volume.[2]

Bone marrow transplants every three months from young to old mice increased lifespan by 34% in syngeneic transplants; there were no significant lifespan increase from allogeneic transplants.[3]

Transplants of young bone marrow into old mice without myeloablation increased mean lifespan by 6%. Two out of eight transplanted mice died during the transplantation process.[4]

A randomized study on 30 elderly patients given allogeneic mesenchymal stem cells (usually derived from bone marrow) found that in the 100M-cell group, serum TNF-alpha decreased, the 6-minute walk test and short physical performance battery significantly improved, and forced expiratory volume significantly improved.[5]

Other Stem Cell Transplants

Muscle-derived stem/progenitor cells proliferate slower in old mice or progeroid mice than young healthy mice. Injecting with young wild-type MDSPCs doubled lifespan of progeroid mice and significantly reduced aging symptoms (like dystonia, trembling, kyphosis, ataxia, muscle wasting, loss of vision, urinary incontinence and decreased spontaneous activity.)[6]

Mice whose hypothalamic stem cells had been ablated had 10% shorter lifespans than control mice; mice whose hypothalamuses were injected with newborn hypothalamic stem cells had 10% longer lifespans than controls. The mice treated with newborn stem cells had significantly improved locomotion, muscle endurance, coordination, sociality, and novel recognition.[7]

Further Experiments

Rodent lifespan studies on bone marrow transplants or mesenchymal stem cell transplants would be very valuable to replicate independently, since previous studies varied widely in the amount of lifespan extension they report. Other aging symptoms (like frailty and cognitive decline) would also be valuable to measure in rodent studies of bone marrow transplants.

References

[1]Shen, Jinhui, et al. “Transplantation of mesenchymal stem cells from young donors delays aging in mice.” Scientific reports 1 (2011): 67.

[2]Li, Shu-Hong, et al. “Reconstitution of aged bone marrow with young cells repopulates cardiac-resident bone marrow-derived progenitor cells and prevents cardiac dysfunction after a myocardial infarction.” European heart journal 34.15 (2012): 1157-1167.

[3]Karnaukhov, Alexey V., et al. “Informational theory of aging: the life extension method based on the bone marrow transplantation.” Journal of Biophysics 2015 (2015).

[4]Kovina, Marina, et al. “Effect on lifespan of high yield non-myeloablating transplantation of bone marrow from young to old mice.” Frontiers in genetics 4 (2013): 144.

[5]Tompkins, Bryon A., et al. “Allogeneic mesenchymal stem cells ameliorate aging frailty: A phase II randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical trial.” The Journals of Gerontology: Series A 72.11 (2017): 1513-1522.

[6]Lavasani, Mitra, et al. “Muscle-derived stem/progenitor cell dysfunction limits healthspan and lifespan in a murine progeria model.” Nature communications 3 (2012): 608.

[7]Zhang, Yalin, et al. “Hypothalamic stem cells control ageing speed partly through exosomal miRNAs.” Nature 548.7665 (2017): 52.