Senolytics

This is Part 5 in our series of posts on types of treatments that might extend healthy lifespan.

What Are Senescent Cells?

Senescent cells are cells that have lost the ability to divide, as most cultured cells do after several generations. Organisms accumulate more senescent cells as they age.

Senescent cells are permanently arrested in the G1 phase of the cell cycle, never reaching the point of cell division, but also persisting in the body for a long time, as they resist apoptosis. They also have a distinct transcriptional signature; more activity on the p53 and pRB pathways, which inhibit the cell cycle. [1]

Very short telomeres can trigger senescence. But that’s only one of many causes: DNA damage, oncogenes, and stress can also make cells senescent.

Senescent cells are thought to play a causative role in the diseases of aging. They are highly concentrated at the sites of age-related diseases, such as atherosclerosis and osteoarthritis.

Senescent cells have a distinctive pattern of secretion (this is known as the senescent-associated secretory phenotype, or SASP), in which they release pro-inflammatory cytokines and extracellular matrix proteins into the surrounding tissue microenvironment. This is a plausible mechanism by which senescent cells can cause a variety of diseases.

Chronic inflammation due to senescent cells can cause age-related vascular dysfunction and atherosclerosis. The proinflammatory factor IL-6, released by senescent cells, causes insulin resistance, which can lead to diabetes. Inflammatory cytokines also cause inflammation of cartilage, which leads to osteoarthritis. Senescence of astrocytes is associated with the deterioration of Alzheimer’s disease, and chronic brain inflammation is thought to be one of the causes of neuron death in Alzheimer’s.[2]

Intro to Senolytics

Since senescent cells seem to cause some of the symptoms and disorders of aging, one avenue towards developing anti-aging therapies is to find drugs that selectively kill senescent cells. These therapies are known as senolytics.

In the past few years, several senolytic drug candidates have been developed and tested on mice. They do, indeed, kill senescent cells, and have various health benefits for aged mice or fast-aging strains of mice. Senolytics sometimes show effects immediately after a single dose, even on old mice, as well as having preventative effects on aging if given regularly.

There seems to be no evidence yet that senolytics extend mouse lifespan; I couldn’t find any studies that tested their effects on longevity. Several of the senolytic drugs discovered so far are also chemotherapy drugs, which means they have serious side effects such as neutropenia; there’s more work to be done to find drugs and protocols that are safe in humans.

Dasatinib and Quercetin

Dasatinib and Quercetin are a leukemia drug and a plant flavonoid, respectively. (Quercetin is found in fruits and vegetables; its highest concentration is found in capers.) In combination, they kill senescent cells. In vitro, dasatinib + quercetin kills off 50% of senescent cells while the proliferating (healthy) cells reach 350% abundance.

A combination of dasatinib and quercetin, given once, also reduced senescent cells in old mice, as well as improving cardiac function.

Another model of mouse aging is to simulate age-related decline with radiation treatments. Mice with irradiated legs had their hair turn gray on those legs and lost treadmill exercise capacity; a single treatment with dasatinib + quercetin significantly improved endurance relative to controls, essentially equalling the performance of sham-irradiated mice, and the effect remained significant 7 months after a single dose.

Mice with progeria (a mutation that causes rapid aging, in the gene Errc1) treated weekly with dasatinib + quercetin had significantly lower “aging scores” ( a composite of symptoms) at 15 weeks than untreated mice.[3]

Dasatinib + quercetin given monthly for 3 months in aged mice reduced the number of senescent cells in the aorta. Treated mice’s arteries were more responsive to acetylcholine, and had increased peak contractile response. In APOE-/- mice, a model of atherosclerosis, dasatinib + quercetin didn’t reduce plaque size but did reduce plaque calcification.[4]

Fibrotic lung cells in a mouse model of pulmonary fibrosis treated with dasatinib + quercetin saw a significant, selective drop in the number of senescent cells, an increase in caspase, a drop in P16 expression (both signs that the senescent cells were going through apoptosis), and a reduction in the senescence-associated secretory phenotype. (That is, less IL-6, less collagen & fibronectin, and reduced amounts of various clotting inhibitors.) The mouse model of pulmonary fibrosis is associated with increased numbers of senescent cells.[5]

It’s not known how dasatinib affects lifespan in healthy animals, but quercetin treatment appears to _shorten _it. Mice given a diet with supplemental quercetin (10 mg/day) had significantly shorter lifespans than mice given a standard diet.[6] This is a higher dose than that given in the senolytic studies, but it’s worth keeping in mind that high dose quercetin can be dangerous.

BCL-xL Inhibitors

The BCL-2 family of proteins have an anti-apoptotic effect that preserves the life of senescent cells. Inhibiting the activity of these proteins results in drugs with senolytic effects.

Navitoclax, which targets BCL-2, BCL-xL, and BCL-w, is senolytic in some cell types (HUVEC epithelial, MEF fibroblast cells, and IMR90 fetal lung cells) but not others (preadipocytes.) You need to knock down all three BCL types to get a senolytic effect, and these do not rise in senescent preadipocytes, which explains the selective effect. Navitoclax is not a risk-free drug; it is an anti-cancer drug, and causes neutropenia.[7]

Fisetin, a plant flavonoid found in fruits, and A1331852 and A1155463, BCL-xL inhibitors with milder side effects than navitoclax, are senolytic in some types of cells but not others: they work on HUVECs and IMR90s (epithelial cells and fetal lung cells), but not human preadipocytes.[8]

Ruxolitinib

Ruxolitinib is a JAK inhibitor, which means it interferes with the JAK-STAT pathway that governs proliferation, differentiation, and oncogenesis. It is a cancer drug, and has side effects including neutropenia.

Ruxolitinib in vitro attenuates the SASP in HUVECs and preadipocytes. In old mice, 2 months of ruxolitinib therapy reduced systemic inflammation, enhanced physical capacity, preserved fat tissue homeostasis, and improved metabolic function.[9]

Ruxolitinib drops inflammatory secretion (IL-6, GM-CSF, GCSF, etc) significantly in senescent human preadipocytes, reduces macrophage migration (a measure of inflammation), and enhances physical activity, hanging endurance, and grip strength in aged mice after 10 weeks of treatment.[10]

HSP90 Inhibitors

A screening study on fetal cells from fast-aging (Ercc-/-) mice found that dasatinib+quercetin, navitoclax, rapamycin, and NDGA (creosote extract) were senolytic, but not resveratrol or curcumin. (Neither resveratrol nor curcumin extend mouse lifespan.) Rapamycin and NDGA reduced the number of senescent cells but not the total number of cells – they are “senomorphic”, preventing the senescent phenotype, rather than senolytic.

A larger screen found 6 senomorphic drugs and 7 senolytics. However, only two drugs, geldanamycin and tanespimycin, were able to reduce senescent cells without harming healthy cells. These are both HSP90 inhibitors, which prevent protein stabilization and thus allow protein degradation. Geldanamycin is senolytic in a variety of cell types: MEF, MSC, IMR90, WI38. Alvespimycin (a geldanamycin analogue) drops IL-6 and P16 in fast-aging MEF cells.

Alvespimycin** **in Ercc-/- mice administered 3 times a month for the whole 6-month lifespan of the mice significantly reduced symptoms such as kyphosis, dystonia, tremor, loss of forelimb grip strength, coat condition, ataxia, gait disorder, and overall body condition.[11]

Geldanamycin is an anti-tumor drug which is not used in humans because it is hepatotoxic. Its analogue alvespimycin is safer but still causes neutropenia and cardiotoxicity.[12] Tanespimycin, another geldanamycin analogue, causes common chemotherapy side effects such as nausea, fatigue, and low platelet count.[13]

FOXO4 Inhibitors

FOXO4 expression is elevated in senescent cells compared to normal cells, and inhibiting its expression with an shRNA resulted in apoptosis and reduction in cell density and viability in senescent cells, but not control cells.

FOXO4-DRI, a peptide that prevents FOXO4 from interacting with p53, can selectively kill senescent cells – a 11.73-fold difference vs. control cells. Quercetin and dasatinib were not specific to senescent vs. non-senescent IMR90 cells. Navitoclax and ombitasvir** **did cause targeted apoptosis, but not as targeted as FOXO4-DRI.

FOXO4-DRI restored liver function and body weight to normal in a doxorubicin-treatment model of mouse aging. FOXO4-DRI also counters senescence and symptoms of aging in fast-aging (Xpd) mice: more hair, more activity, better kidney function. It also counteracts senescence and improves responsiveness, fur density, and renal function in naturally aged mice.

FOXO4-DRI does not cause thrombocytopenia or any other whole blood count abnormality in mice, unlike navitoclax and other BCL or HSP inhibitors.[14]

Investment Landscape and Funding Opportunities

Senolytics are not being ignored by mainstream biotech investors. In particular, Unity Biotech, the company founded on the research of the team that discovered FOXO4-DRI, closed a $116 million Series B round of funding in 2016.

However, there are still major open questions that are hard to address. We don’t yet know whether senolytics extend lifespan in animals.

A report by a conference on gerontology explains that aging science has a chronic problem with not being able to efficiently test the effects of drugs on longevity in mammals. “Human clinical trials of therapeutics that target basic aging processes are rare. It is clear that barriers between discovery and translation—“the valley of death”—are blocking needed progress in the field.” The problem is simply that mice live several years, and that is a long time for a scientific study, so the volume of research on longevity remains low. The report suggests various proxies for mouse lifespan, some of which are already in use. “For example, studies on survival following administration of candidate drugs beginning in already old mice may be a way to accelerate development.“ Healthspan, mouse models of disease, and resilience/frailty measures can also speed up development of mammalian screens; mice with fast-aging syndromes can model naturally aged mice; and accurate biomarkers for aging would be an effective proxy for lifespan.[15]

The Major Mouse Testing Program is currently raising funds, organized by the Life Extension Advocacy Organization. They are doing the most straightforward thing: testing the known senolytic compounds (dasatinib, quercetin, navitoclax) on already-aged mice to see if they extend lifespan. There will also be an “active control” of caloric restricted mice (we know that caloric restriction extends lifespan). They hit their major funding goal last year, but haven’t yet reported results, so it’s worth contacting them and seeing what progress they’ve made so far before further funding.

Key Labs

James Kirkland, Mayo Clinic

Paul Robbins, Scripps

Laura Niedernhofer, Scripps

Judith Campisi, Buck Institute

Jan van Deursen, Mayo Clinic

Speculation & Strategy

I think there will be three major avenues for research on senolytics before they’re ready for clinical trials.

- Testing the drugs we already have on mice

- Doing bigger in-vitro screens to find other senolytic drug candidates

- Designing safer or cheaper versions of known senolytic drugs.

A bit more on #3: it will never be a good risk-benefit tradeoff to give a healthy person a chemotherapy drug as an aging preventative. The side effects are seriously unpleasant at best, and usually dangerous as well. So, we might search for safer analogues of those drugs. (But note that chemotherapy is sixty years old and researchers have been trying to find safer analogues for all of that time.) FOXO3-DRI might turn out to be safer – it certainly seemed safer in the one mouse study we have – but it’s a peptide, which means it has to be synthesized via recombinant DNA, which is _extremely _expensive. That doesn’t necessarily mean it can’t be brought to market, but it means that if there were a small-molecule drug that worked along a similar pathway, it would make a big difference to the drug’s accessibility.

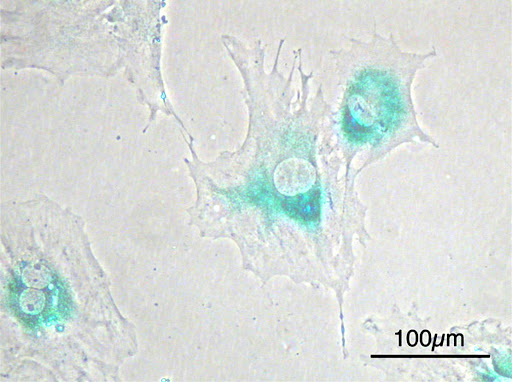

#1 is probably the cheapest type of study; the MMPT is doing it for less than $100,000. #2 is something that I suspect could benefit from being done in a biotech company or high-tech research institute rather than a university; large-scale high-throughput screening and automation benefit _enormously _from a team of technicians and engineers who invest in building tools that scale, which is rarer in academia. (Senescent cells are now identified by immunofluorescence, but they are also visually distinct from normal cells under the microscope; they are larger and flatter.[16] So it might be possible to speed up drug screening by using image recognition to identify senescent cells.) #3 is hard and may not work. So, as an efficient use of resources, my tentative opinion is that they should be prioritized in that order.

References

[1]Campisi, Judith, and Fabrizio d’Adda di Fagagna. “Cellular senescence: when bad things happen to good cells.” Nature reviews. Molecular cell biology 8.9 (2007): 729.

[2]Zhu, Yi, et al. “Cellular senescence and the senescent secretory phenotype in age-related chronic diseases.” Current Opinion in Clinical Nutrition & Metabolic Care 17.4 (2014): 324-328.

[3]Zhu, Yi, et al. “The Achilles’ heel of senescent cells: from transcriptome to senolytic drugs.” Aging cell 14.4 (2015): 644-658.

[4]Roos, Carolyn M., et al. “Chronic senolytic treatment alleviates established vasomotor dysfunction in aged or atherosclerotic mice.” Aging Cell 15.5 (2016): 973-977.

[5]Lehmann, Mareike, et al. “Senolytic drugs target alveolar epithelial cell function and attenuate experimental lung fibrosis ex vivo.” European Respiratory Journal 50.2 (2017): 1602367.

[6]Jones, Eleri, and R. E. Hughes. “Quercetin, flavonoids and the life-span of mice.” Experimental gerontology 17.3 (1982): 213-217.

[7]Zhu, Yi, et al. “Identification of a novel senolytic agent, navitoclax, targeting the Bcl‐2 family of anti‐apoptotic factors.” Aging Cell 15.3 (2016): 428-435.

[8]Zhu, Yi, et al. “New agents that target senescent cells: the flavone, fisetin, and the BCL-XL inhibitors, A1331852 and A1155463.” Aging (Albany NY) 9.3 (2017): 955.

[9]Xu, Ming, Tamar Tchkonia, and James L. Kirkland. “Perspective: Targeting the JAK/STAT pathway to fight age-related dysfunction.” Pharmacological research 111 (2016): 152-154.

[10]Xu, Ming, et al. “JAK inhibition alleviates the cellular senescence-associated secretory phenotype and frailty in old age.” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 112.46 (2015): E6301-E6310.

[11]Fuhrmann-Stroissnigg, Heike, et al. “Identification of HSP90 inhibitors as a novel class of senolytics.” Nature Communications 8.1 (2017): 422.

[12]Lancet, J. E., et al. “Phase I study of the heat shock protein 90 inhibitor alvespimycin (KOS-1022, 17-DMAG) administered intravenously twice weekly to patients with acute myeloid leukemia.” Leukemia 24.4 (2010): 699.

[13]Modi, Shanu, et al. “Combination of trastuzumab and tanespimycin (17-AAG, KOS-953) is safe and active in trastuzumab-refractory HER-2–overexpressing breast cancer: a phase I dose-escalation study.” Journal of clinical oncology 25.34 (2007): 5410-5417.

[14]Baar, Marjolein P., et al. “Targeted apoptosis of senescent cells restores tissue homeostasis in response to chemotoxicity and aging.” Cell 169.1 (2017): 132-147.

[15]Burd, Christin E., et al. “Barriers to the preclinical development of therapeutics that target aging mechanisms.” Journals of Gerontology Series A: Biomedical Sciences and Medical Sciences 71.11 (2016): 1388-1394.

[16]Rodier, Francis, and Judith Campisi. “Four faces of cellular senescence.” The Journal of cell biology (2011): jcb-201009094.