Melatonin and Pineal Gland Extracts

This is Part 1 in our series of posts on types of treatments that might extend healthy lifespan.

What Is Melatonin?

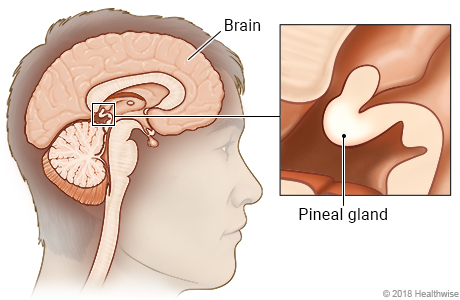

Melatonin is the “sleep hormone” which regulates the circadian rhythm; it is the main product of the pineal gland in the brain. It is safe and available as an over-the-counter supplement. There’s a fair amount of animal evidence that melatonin supplements can extend life.

What is Epithalamin?

Epithalamin is a peptide (a short chain of amino acids) produced by the pineal gland. There’s evidence that epithalamin extends animal, and perhaps even human, life – but it’s mostly from two Russian researchers and hasn’t been confirmed in the West.

Melatonin and Lifespan

There’s inconsistent, but suggestive, animal evidence that melatonin can extend life slightly.

Male, but not female, C3H mice given 2.5 mg/kg/day melatonin at night starting at 4 months of age lived 20% longer than control mice.[4]

Female CBA mice given melatonin 5 days a week in water at 20 mg/L had a mean lifespan 5.4% longer than controls, but had more tumors than controls.[5]

Female SHR mice starting at 3 months on 2 mg/L or 20 mg/L melatonin did not increase mean lifespan, though the high dose did increase maximum lifespan by 11%. Mice treated with low-dose melatonin had fewer tumors than controls.[6]

Female SAMP8 mice (which have accelerated senescence) lived 10% longer with lifelong administration of melatonin in water at 10 mg/kg.[9]

Pineal Gland Extracts and Lifespan

Epithalamin has been found to extend lifespan in various strains of mice and rats.

The pineal peptide preparation, epithalamin, gave outbred rats a median lifespan of 24% longer than controls, 32% in C3H/Sn mice, and 14% in SHR mice.[1]

Female rats given pineal peptide extract starting at 16-18 months at 0.1 mg five times a week lived 10% longer than controls; at 0.5 mg they lived 25% longer than controls. Significantly fewer of the treated than control rats had estrous disturbances, and the treated rats had significantly fewer tumors.[3]

Outbred aged female rats given 0.5 mg epithalamin a day had a median lifespan 6.2% longer than controls, and were significantly less likely to have estrous disturbances or tumors at the time of death.[10]

Female SHR mice starting at 3 months on epithalamin didn’t have longer mean lifespan than control, but did have 12.3% greater max lifespan.[11]

Female CBA mice given epithalamin had lifespans 5.3% longer than control mice.[13]

Female C3H/Sn mice given epithalamin at 0.5 mg/day lived 31% longer than controls and had half as many tumors.[14]

Human Studies

There were two human studies, both from the same researchers who did the animal studies, that found that epithalamin reduced mortality and the incidence and severity of heart disease.

94 women aged 66-94 from the War Veterans Home in St. Petersburg were randomized to control, thymus extract (thymalin), pineal extract (epithalamin), or both. In 6 years, 81.8% of the control patients died, compared to 41.7% of the thymalin patients, 45.8% of the epithalamin patients (both applied for 2 years) and 20.0% of the patients given epithalamin and thymalin for 6 years. The effect on mortality was significant at p<0.001. Epithalamin also significantly reduced the rate of ischemic heart disease, and returned NK, TSH, cortisol, and insulin levels to healthy levels (at baseline, these elderly women had low NK counts and high TSH, cortisol, and insulin levels.)[12]

Seventy elderly patients with heart disease were randomized to 50 mg injections of epithalamin every 6 months vs. placebo. Clinical symptoms of heart disease were significantly (p < 0.05) more likely to worsen in the placebo group compared to the control group in 3 years; exercise tolerance increased 21%; by the end of the 3-year period, 22% of treated patients had died, compared to 44% of control patients (p < 0.05).[15]

Other Evidence

Pinealectomized rats have shorter lifespans, which would make sense if the pineal gland were producing a longevity-promoting substance.[1]

The farther the free-running circadian period is from 24 hours (in various rodent and primate species), the shorter the lifespan. So the desynchronization of circadian rhythms that coincides with less melatonin production as we age may shorten lifespan.[7]

Fetal transplants of the supraschiasmatal nucleus (the part of the brain that controls circadian rhythms) made aged hamsters live twice as long after surgery, or roughly a 10% increase in lifespan. This points towards renormalizing youthful circadian rhythms as being a feasible longevity intervention.[8]

Lifelong nighttime supplementation with melatonin delayed reproductive senescence in Holtzman rats; they had fewer (p < 0.001) abnormal-length estrous cycles. In other words, melatonin keeps rats “reproductively young.”[2]

Old rhesus monkeys have lower melatonin levels than young monkeys. Epithalamin, but not placebo, raises old rhesus monkeys’ melatonin levels to that of young monkeys. Old monkeys also have higher blood glucose levels (at baseline and in response to glucose challenge) than young monkeys; epithalamin significantly reduces glucose in old monkeys (but not young monkeys.) Old monkeys have a delayed and flatter curve of insulin response to glucose challenge than young monkeys; epithalamin reverses this. Epithalamin therefore seems to help with glucose tolerance.[16]

Pinealectomized rats have higher glucose levels, lower insulin levels, and higher glucagon levels than control rats; treatment of pinealectomized rats with melatonin increases insulin and reduces glucagon. Pinealectomized rats have glucose intolerance, while melatonin supplementation partially recovers glucose tolerance.[17]

Insulin resistance and Type II diabetes in humans are associated with lower melatonin secretion and loss-of-function mutations in melatonin receptors. This suggests that melatonin is protective against insulin resistance.[18]

Major Researchers

Vladimir Anisimov, of the N.N. Petrov Research Institute of Oncology in St. Petersburg, did most of the research on melatonin and epithalamin.

Vladimir Khavinson, Anisimov’s frequent collaborator, at the St. Petersburg Institute of Bioregulation and Gerontology

Funding Landscape

Probably underfunded. Very little out there except peptide sites selling gray-market epithalamin.

Melatonin as a life extension drug was popularized in the 90’s by Walter Pierpaoli, whose studies were later found to have poor methodology and whose self-promotion tactics are rather shady; this may have caused the drug to fall out of favor.

Possible Studies

- Replicating the life-extension effects of epithalamin (on mice, rats, or other animals) in a non-Russian lab.

- Non-Russian human study of epithalamin on elderly subjects or people with metabolic syndrome.

General Notes

Melatonin/epithalamin is big news if true: large life extension effects in very safe drugs. It also has a credible evolutionary rationale for why it should work (see my take here). However, most of the research on melatonin and longevity comes from a handful of Russian labs, and needs to be replicated elsewhere.

References

[1]Anisimov, Vladimir N., Sergey V. Mylnikov, and Vladimir Kh Khavinson. “Pineal peptide preparation epithalamin increases the lifespan of fruit flies, mice and rats.” Mechanisms of ageing and development 103.2 (1998): 123-132.

[2]Meredith, S., et al. “Long-term supplementation with melatonin delays reproductive senescence in rats, without an effect on number of primordial follicles☆.” _Experimental gerontology_35.3 (2000): 343-352.

[3]Dilman, V. M., et al. “Increase in lifespan of rats following polypeptide pineal extract treatment.” Experimentelle Pathologie 17.9 (1979): 539-545.

[4]Oxenkrug, G., P. Requintina, and S. Bachurin. “Antioxidant and Antiaging Activity of N‐Acetylserotonin and Melatonin in the in Vivo Models.” Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences 939.1 (2001): 190-199.

[5]Anisimov, Vladimir N., et al. “Melatonin increases both life span and tumor incidence in female CBA mice.” The Journals of Gerontology Series A: Biological Sciences and Medical Sciences 56.7 (2001): B311-B323.

[6]Anisimov, Vladimir N., et al. “Dose-dependent effect of melatonin on life span and spontaneous tumor incidence in female SHR mice.” Experimental gerontology 38.4 (2003): 449-461.

[7]Wyse, C. A., et al. “Association between mammalian lifespan and circadian free-running period: the circadian resonance hypothesis revisited.” Biology letters 6.5 (2010): 696-698.

[8]Hurd, Mark W., and Martin R. Ralph. “The significance of circadian organization for longevity in the golden hamster.” Journal of biological rhythms 13.5 (1998): 430-436.

[9]Rodríguez, María I., et al. “Improved mitochondrial function and increased life span after chronic melatonin treatment in senescent prone mice.” Experimental gerontology 43.8 (2008): 749-756.

[10]Anisimov, V. N., L. A. Bondarenko, and V. Kh Khavinson. “Effect of pineal peptide preparation (epithalamin) on life span and pineal and serum melatonin level in old rats.” Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences 673.1 (1992): 53-57.

[11]Anisimov, Vladimir N., et al. “Effect of Epitalon on biomarkers of aging, life span and spontaneous tumor incidence in female Swiss-derived SHR mice.” Biogerontology 4.4 (2003): 193-202.

[12]Khavinson, Vladimir Kh, and Vyacheslav G. Morozov. “Peptides of pineal gland and thymus prolong human life.” Neuroendocrinology Letters 24.3-4 (2003): 233-240.

[13]Anisimov, Vladimir N., et al. “Effect of synthetic thymic and pineal peptides on biomarkers of ageing, survival and spontaneous tumour incidence in female CBA mice.” Mechanisms of ageing and development 122.1 (2001): 41-68.

[14]Anisimov, V. N., V. Kh Khavinson, and V. G. Morozov. “Carcinogenesis and aging. IV. Effect of low-molecular-weight factors of thymus, pineal gland and anterior hypothalamus on immunity, tumor incidence and life span of C3H/Sn mice.” Mechanisms of ageing and development 19.3 (1982): 245-258.

[15]Korkushko, O. V., et al. “Geroprotective effect of epithalamine (pineal gland peptide preparation) in elderly subjects with accelerated aging.” Bulletin of experimental biology and medicine 142.3 (2006): 356-359.

[16]Goncharova, N. D., et al. “Pineal peptides restore the age-related disturbances in hormonal functions of the pineal gland and the pancreas.” Experimental gerontology 40.1 (2005): 51-57.

[17]Diaz, Beatriz, and E. Blazquez. “Effect of pinealectomy on plasma glucose, insulin and glucagon levels in the rat.” Hormone and metabolic research 18.04 (1986): 225-229.

[18]McMullan, Ciaran J., et al. “Melatonin secretion and the incidence of type 2 diabetes.” Jama 309.13 (2013): 1388-1396.