More On Image Recognition Progress

In my post on AI progress, I picked a few benchmark tasks, to see how machine learning algorithms have improved over the past few decades. Obviously those aren’t a comprehensive list, so I thought I’d add a few more.

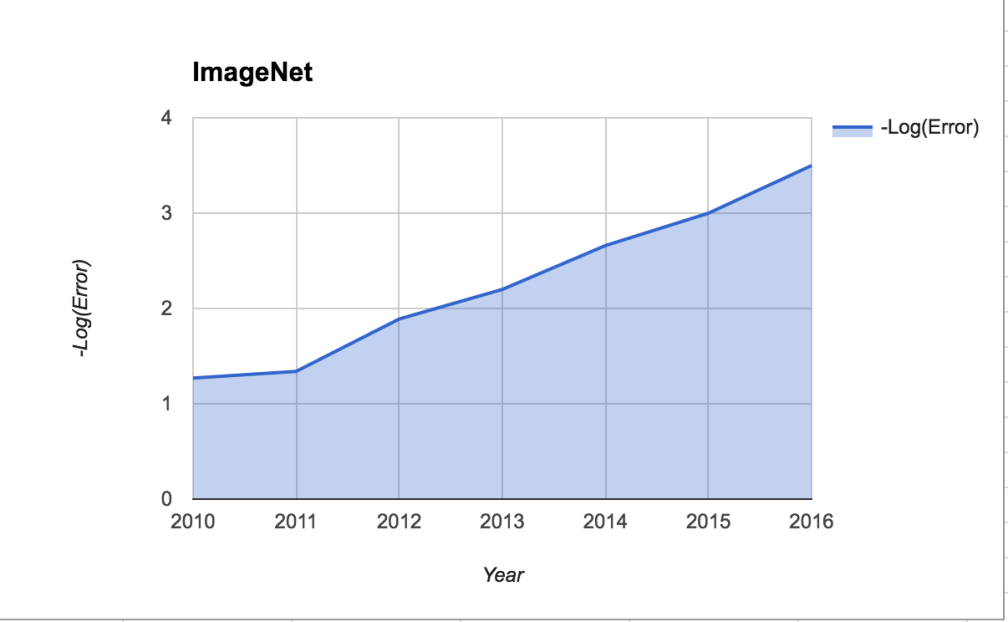

I also claimed in that post that image recognition was “slowing down”, because the rate of improvement in accuracy percent was diminishing. I’ve since been convinced that a more meaningful metric for performance in image classification (or any classification task where perfect accuracy means 100% correct) is the negative log of the error rate. Obviously, as we approach perfect classification, no matter how quickly we do so, the raw percent accuracy score must “flatten out” because it’s bounded above by 100%. Transforming it into a log scale means that an error that decayed exponentially to zero over time would look like “linear progress”, which seems more natural. “Linear progress” on a log scale, given a continuation of Moore’s law, also means something like linear returns to computing power — i.e. scaling and parallelization don’t present much in the way of an impediment.

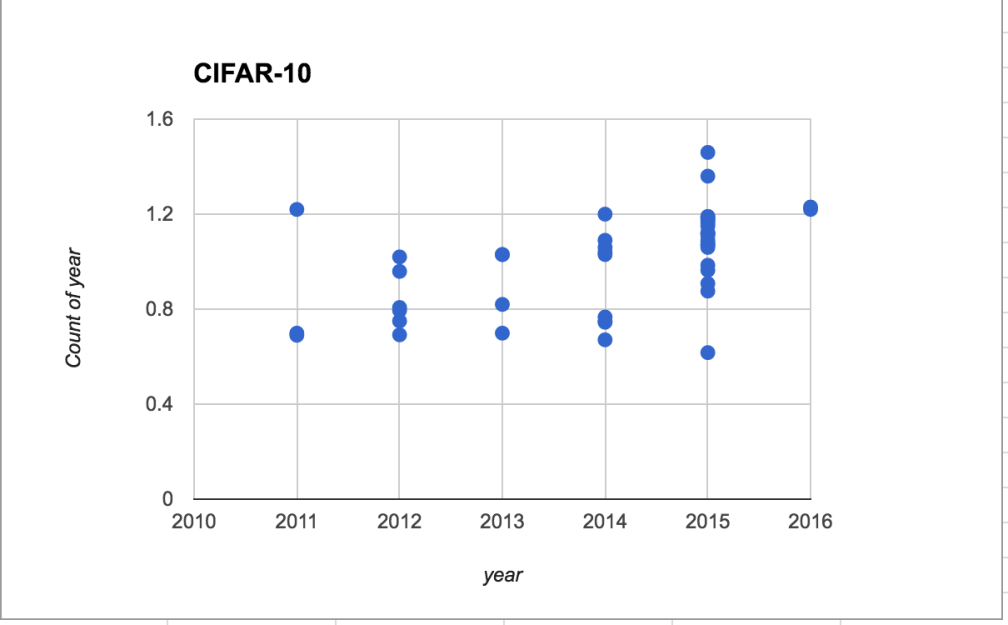

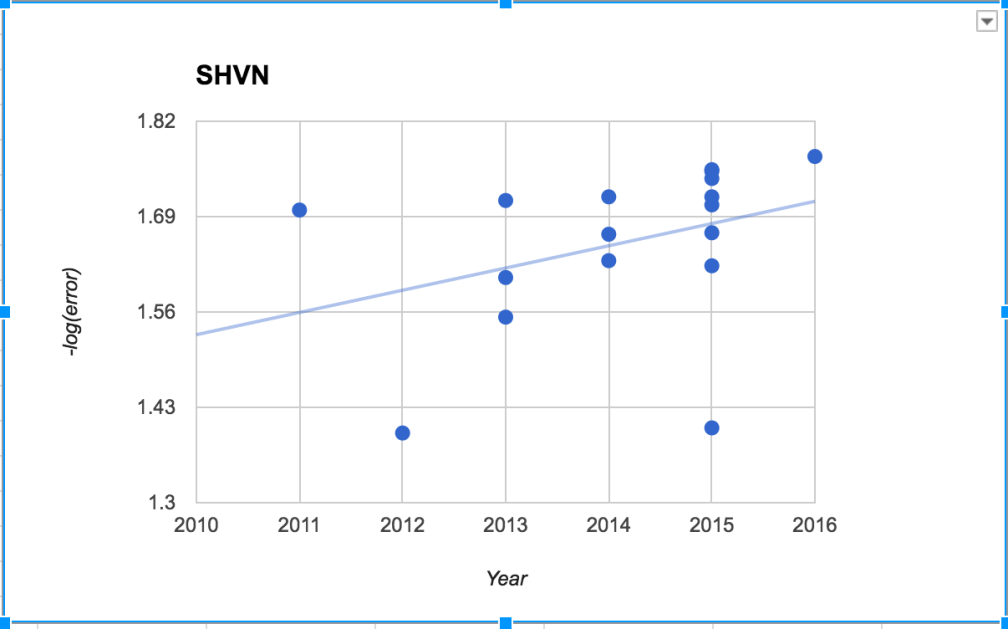

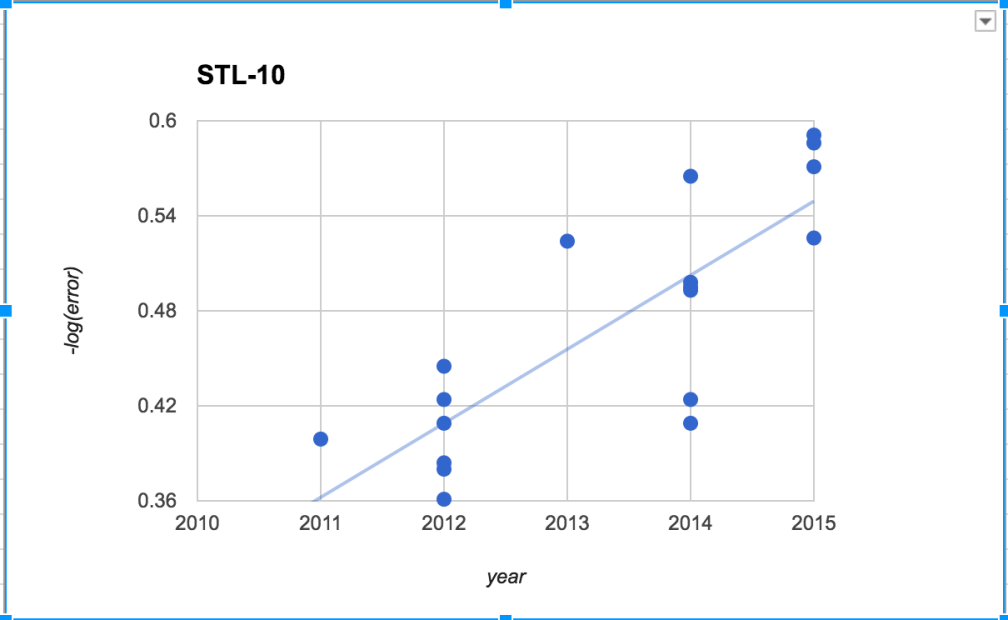

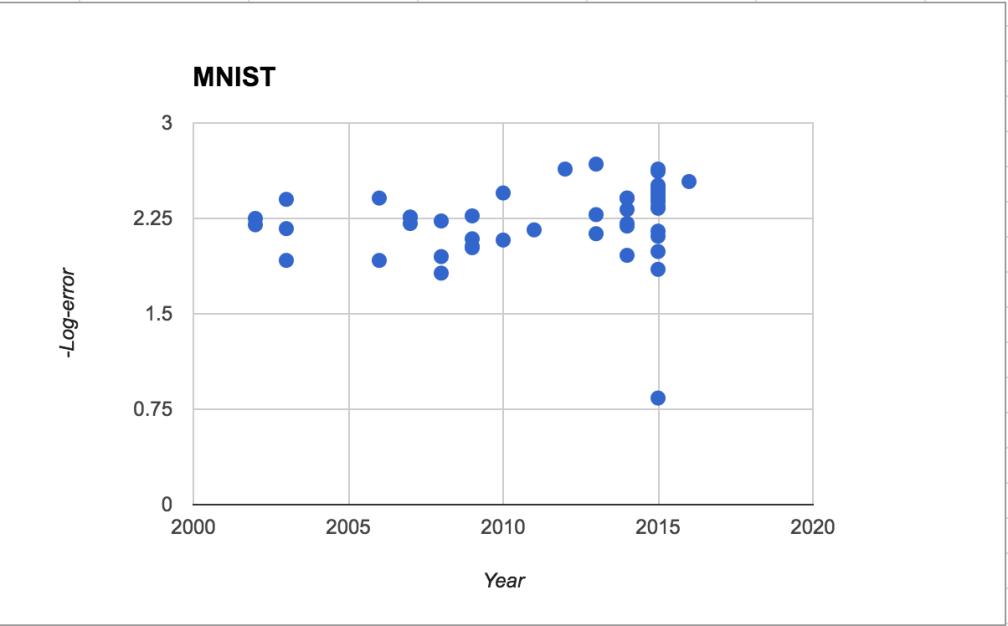

From this dataset, I found (crowdsourced) papers and dates for performance on six image recognition benchmarks datasets, and graphed -log(error) over time.

With the possible exception of MNIST, all of these show a positive trend over time, and some are clearly linear. Most of these data points come from deep learning algorithms, except a few of the very earliest ones.

For reference, here’s the ImageNet performance data from the past post, but transformed to -log(error) instead of accuracy percent. It, too, looks linear.

The picture here looks quite similar to the performance over time of AI at chess and go, which looks roughly linear in Elo score (also a measure that is roughly logarithmic in the “raw” percent of games won.) Progress since the advent of deep learning has been steady. Returns to computing power appear roughly linear in Elo score, and also roughly linear in -log(error).

What does this mean, as a bottom line for the future of AI?

In those areas where deep learning can be successful, it seems like scaling is not an insurmountable problem: if you put more computational resources in, you can get more performance out. The curve’s not going to bend upward — deep learning algorithms don’t get smarter per GPU if you add more GPU’s — but, at least for the past few years, marginal returns to GPUs and training data have been more or less constant, not falling. “Just do exactly what you’re doing, but more so” should yield steady improvements in narrow AI performance, at least for a while.