Industry Matters

In the wake of the election, I’ve been thinking about the decline of manufacturing in America.

The conventional story, the one I’d been told by the news, goes as follows. Cheap labor abroad competes with US manufacturing jobs; those jobs aren’t coming back; most manufacturing jobs are lost to robots, not trade, anyhow; this is tragic for factory workers who lose their jobs, and perhaps they should be compensated with more generous social services, but overall the US’s shift towards a service economy is for the best. Opposition to outsourcing, while perhaps an understandable emotional reaction from the hard-hit working class, is simply bad economics. At best, the goal of keeping manufacturing jobs at home is a concession to the dignity and self-image of workers; at worst, it’s wooly-headed socialism or xenophobia.

But what if that story were not true?

Here’s an alternative story, which I think there’s some data to suggest.

Industry — as in, factories in the US making things like cars and trains — is important to long-run technological innovation, because most commercial R&D is in the manufacturing sector, and because factories and research facilities tend to physically co-locate.

High-tech, high-cost-per-unit industries in particular, like the auto industry, are like keystone species in an industrial ecosystem, because you need many different kinds of technology to support them, and because the high cost per unit makes them the _first _ industries where it’s worth it to invest in new process improvements like robotics. If you don’t have heavy industry at home, eventually you won’t have innovation at home.

And if you don’t have innovation at home, your economy may eventually stagnate. Foundational technologies, things like integrated circuits or metallurgy, have high fabricatory depth; better microchips give rise to more computing power which gives rise to untold multitudes of software applications. If your economy lives exclusively on the “leaves” of the tech tree, you aren’t going to be able to capture the value from a long future of continued inventions. There may be high-paying jobs in the service economy, but an entire economy built on services will eventually flatten out.

In other words: maybe industry matters.

And, while industrial jobs may initially leave the US because they’re cheaper elsewhere, foreign labor doesn’t stay cheap forever. As countries industrialize and become wealthier, they gain expertise and advance technologically, and eventually compete on quality, not just on price. Rich countries hope to “move up the value chain”, outsourcing cheap and crude tasks to poorer countries while focusing their own efforts on higher-tech, higher-priced tasks. The problem is that this doesn’t always work — since collocation matters, it may be that you need at least some of the basic factory work to stay at home in order to be able to do the high-tech work, especially in the long run.

“Industry matters”, if true, might be an argument in favor of tariffs, in a vaguely Hamiltonian industrial policy. Now, the laws of economics still hold; tariffs will always cause some degree of damage. I’m not confident that the numbers work out such that even an ideal tariff would be worth it, let alone the trade policy likely to be administered by the actually-existing USG.

“Industry matters” might also be an argument in favor of deregulation designed around making it easier to move around “atoms not just bits.” If environmental and labor regulations make it extremely difficult to build factories in the US, and if industry has an outsized impact on long-run growth, then the cost of regulation is even higher than previously assumed. If a factory doesn’t open, the cost is not only borne by the people today who could have worked in or profited from that factory, but by future generations who won’t be able to work at the new companies which would have been produced from innovations downstream of that factory.

If industry matters, it might be worth it to trade a bit of efficiency today for long-run growth. Not as a concession to Rust Belt voters, but as a genuine value-creating move.

The US is transitioning to a service economy

According to the Bureau of Labor Statistics’ Employment Outlook Handbook, occupations with declining employment include:

- Agricultural workers

- Clerks (file, correspondence, accounting, etc)

- Cooks (fast food and short order)

- Various manufacturing occupations like “machine tool setters” and “electronic equipment assemblers”

- Railroad-related occupations

- Drafters, medical transcriptionists

- Secretaries and administrative assistants

- Broadcasters, editors, reporters, radio and television announcers

- Travel agents

while the jobs with the fastest growth rates include:

- Nurses, home health aides, physician’s assistants, physical therapists

- Financial advisors

- Statisticians, mathematicians

- Wind turbine service technicians, solar photovoltaic installers

- Photogrammetry (i.e. mapping) specialists

- Surgeons, biomedical engineers, nurse midwives, anaesthesiologists, medical sonographers

- Athletic trainers, massage therapists, interpreters, psychological counselors

- Bartenders, restaurant cooks, food preparers, waiters and waitresses

- Cashiers, customer service representatives, hairdressers, childcare workers, teachers

- Carpenters, construction laborers, electricians, rebar workers, masons

Basically, medicine, education, customer service, construction, and the “helping professions” are growing; factory work, farming, and routine office tasks are shrinking, as are industries like news and travel agents that have been disrupted by the internet.

As far as mass layoffs go, in May 2013 the largest sector by number of mass layoffs was manufacturing, where the largest number of people laid off were in “machinery” and “transportation equipment.” Construction followed, where most layoffs were in “heavy and civil engineering” construction.

By sector, mining and manufacturing are losing employment, while construction, leisure and hospitality, education and health, and financial services, are gaining employment.

This part of the conventional story is true: manufacturing jobs really are disappearing.

US manufacturing productivity and output are stagnating

It’s not just jobs, but also productivity and output, where manufacturing in the US is weakening. US manufacturing still produces a lot, but its growth is slowing. We’re not getting better at making things the way we used to.

In the US, the biggest output gains per industry, in billions of dollars, between 2002 and 2012, were in the federal government, healthcare and social assistance, and professional services, at 2.6%, 2.6%, and 2.4% respectively. Manufacturing only grew by 0.2%.

Manufacturing output as a whole between 1997 and 2015 was only growing at 0.8% a year, meaning that it’s slowed down in the last 20 years. Broken down by subsector, the highest manufacturing growth rates were in motor vehicles and other transportation equipment, at an average of about 2% yearly growth; other kinds of manufacturing, such as textiles and apparel, were stagnant or even declined in output. By contrast, the largest output growth between 1997 and 2015 was in information tech, at an average of 5.6% yearly growth, probably coinciding with the rise of the Internet economy.

In other words, US manufacturing isn’t shedding jobs merely because it’s becoming ultra-automated and efficient. US manufacturing growth has slowed down a lot in output as well.

US manufacturing also stagnated in labor productivity and multifactor productivity. Multifactor productivity (the efficiency of labor & capital) in manufacturing has declined at an 0.5% rate from 2007-2014, while it was increasing at a 1.7% rate in 2000-2007, 1.9% in 1995-2000, and 1.1% in 1990-1995. Manufacturing productivity was roughly flat from the 1970’s through 2000.

Manufacturing total factor productivity is still increasing, but has been leveling off.

Manufacturing output, similarly, is still increasing, but has been leveling off in recent decades.

While overall manufacturing productivity is still growing over the period 1987-2010, manufacturing output flattened in about 2000.

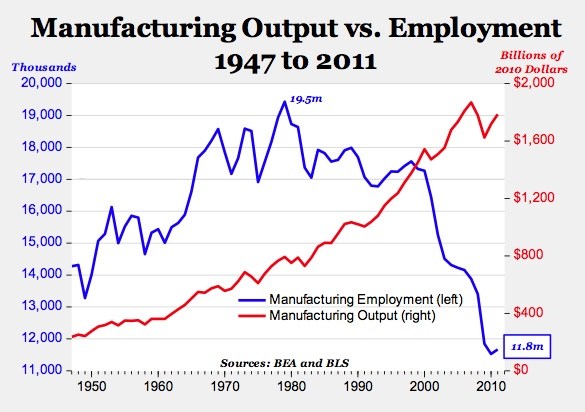

While manufacturing output seems to have grown roughly steadily since the 1950s, with a slow decline or stagnation in employment from about 1970-2000, note how the output curve seems to be bending at around 2000, just as manufacturing employment plummets.

You can also see this slight bend in the curve, beginning in around 2000, in manufacturing value added.

The story of “we’re getting more efficient and thus using fewer workers” is only part true. We’re getting more efficient, but at a slowing rate. We’re producing more output than we did in the 70’s, but that seems to have leveled off in around 2000. Yes, there’s more output and fewer workers, but it looks like recently, since about 2000, multifactor productivity and output are slowing down.

The Big Three auto manufacturers in the US, between 1987 and 2002, had dropping market share and stock price, largely due to international competition. They lagged the competition in durability and vehicle quality, so were forced to cut prices. They also had a labor productivity disadvantage relative to Japan. It took nearly two decades for US car manufacturers to catch up to Japanese production process improvements.

In other words, the story of the decline in US manufacturing jobs is not _merely that we’re a rich country with expensive labor, or a high-tech country that uses automation in place of workers. If that were true, output and productivity would be continuing to grow, and they’re not. US manufacturing is stagnating in _quality and efficiency.

Robots aren’t taking American jobs

The decline in US manufacturing began in the 1970’s and 1980’s, as trade liberalization made it easier to move production abroad, and new corporate governance rules made US managers focus on stock prices and short-term performance (which could be boosted by moving factories to cheaper countries.)

Manufacturing automation, by contrast, is much newer, and can’t account for anywhere near that much job loss. There are only 1.6 million industrial robots worldwide, mostly in the auto and electronics industries; an automotive company has 10x the roboticization of the average manufacturing company. That is to say, robots are only being used in the highest-tech sectors of the manufacturing world, and not very widely at that. Industrial robots are a rapidly growing but very recent development; there was a 15% increase in the world’s supply of robots just in 2015.

Moreover, countries with more growth in industrial robotics don’t have more job loss. Most new robots are actually abroad rather than in the US. The largest market is in China, with 27% of global supply; the second largest market is in Europe. The US boosted its purchases of robots by only 5% this year, at well below the global rate of robotics growth.

It is simply false that robots are causing any significant part of US manufacturing unemployment. There aren’t very many, they haven’t been around very long, they’re mostly in other countries, and they don’t hurt employment in those countries.

According to the Bureau of Labor Statistics, no US manufacturing layoffs in 2013 were due to automation.

Most of the news articles about the dangers of technological unemployment are based on projections about which jobs are in principle automatable. This is speculative, and doesn’t take into account new industries that may open up as technology improves (basically the argument from Say’s law.) The “post-work future” is largely science fiction at this point. Lost manufacturing jobs are real — but they weren’t lost to robots.

Trade caused manufacturing job loss

The US-China Relations act in 2000 that normalized trade relations permanently was a “shock” to US manufacturing that US jobs were slow to recover from. Not only did employment plummet, but manufacturing productivity also dropped steeply.

Only 2% of job losses are due to offshoring. But this understates the true amount: if plants close in the US while companies buy from foreign affiliates, that’s effectively “jobs moving overseas” under a different name. Foreign affiliates now make up 37% of the total employees of US multinational companies, a figure that has been steadily rising since the 80’s; it was 26% in 1982.

Moreover, trade can also cause US job losses if foreign-owned companies outcompete US companies. The most common reason given for manufacturing layoffs in 2013 was “business demand”, mostly contract completion. Restructuring and financial problems such as bankruptcy were also common reasons. The main reason for manufacturing layoffs seems to be _failure _of US factories — poor demand or poor company performance. Some portion of this is probably due to international competition.

In short, it’s freer trade and poor competitiveness on the international market, not automation, that has hurt American manufacturing. It’s not the robots that are the problem — if anything, we don’t have _enough _robots.

Manufacturing drives the future, and location matters

A McKinsey report on manufacturing notes that while manufacturing is only 16% of US GDP, it’s a full 37% of productivity growth. 77% of commercial research and development comes from manufacturing. Manufacturing, in other words, is where new technology comes from, and new technology drives growth. If you care about the future economy, you care about manufacturing.

R&D, especially later-stage development rather than basic academic research, must be physically proximate to the lead factory even if some production is globalized, for reasons of communication and feedback between research and production. You can’t outsource or trade all your manufacturing without losing your ability to innovate.

Moreover, globalized supply chains have real costs: as trade and outsourcing increase, transportation costs and supply chain risks have also been increasing. Physical proximity places some limits on how widely dispersed manufacturing can be. Trade growth has outpaced infrastructure growth in the US, driving transportation costs up. The cost of freight for steel and iron ore is almost as high as the material itself.

Steel production, in particular, has plummeted in industrialized countries since the 70’s and 80’s, as part of the switch to a service economy. China’s steel and cement production since the 80s seems to have grown rapidly, while its car production seems to be growing roughly linearly. South Korea’s steel production is growing steadily. US car production, by contrast, has been shrinking (in terms of number of units), as has its steel production. Because (due to their weight) metals have unusually high transportation costs, proximity matters an unusual amount, and so a fall in steel production might mean a fall in heavy industry output generally, which is difficult to recover from.

The main theory here is that, once you cease to be an industrial economy, it’s hard to profitably keep factories at home, which means it’s hard to innovate technologically, which means long-run GDP growth is threatened.

The largest manufacturing industries are machines, electronics, and metals

The largest manufacturing companies in China make cars (SAIC, Dongchen, China South Industries Group), chemicals (Sinochem, Chemchina), metals (Minmetals, Hesteel, Shougang, Wuhan), various engineering (Norinco, China Metallurgical group, Sinomach), electronics (Lenovo), phones (Huawei), ships (China Shipbuilding).

The US’s largest manufacturers are general engineering (GE), automotive (GM, Ford), electronics (HP, Apple, IBM, Dell, Intel), pharmaceuticals (Cardinal Health, Pfizer), consumer goods (Procter & Gamble, Johnson&Johnson), aerospace (Boeing, Lockheed Martin), food and beverage (Pepsi, Kraft, Coca-Cola), construction equipment (Caterpillar), and chemicals (Dow).

Germany’s largest manufacturing companies are automotive (Volkswagen, Daimler, BMW), chemicals (BASF), engineering (Siemens, Bosch, Heraeus), steel (ThyssenKrupp), pharmaceuticals (Bayer), and tires (Continental).

Japan’s largest manufacturers are automotive (Toyota, Nissan, Honda), engineering (Hitachi, Panasonic, Toshiba, Mitsubishi, Mitsui, Sumitomo, Denso), electronics (Sony, Fujitsu, Canon), steel (Nippon Steel, JFE), and tires (Bridgestone).

Korea’s largest manufacturers are electronics (Samsung, LG), automotive (Hyundai, Kia), and steel (POSCO).

Machinery and appliances, and electronics and parts, are by far the largest exports from Mexico.

Top exports from China, at a coarse level of granularity, are machines (48%), textiles (11%), and metals (7.8%). At a more granular level, this involves computers, broadcasting equipment, telephones, integrated circuits, and office machine parts.

US‘s top exports are machines (24%), transportation (15%), chemicals (13%), minerals (11%), and instruments (6.3%). More granularly, this is integrated circuits, gas turbines, cars, planes and helicopters, vehicle and aircraft parts, pharmaceuticals, and refined petroleum.

Germany‘s top exports are machines (27%), transportation (23%), chemicals (13%), metals (8.1%), or in more detail: cars, vehicle parts, pharmaceuticals, and a variety of smaller machine things (valves, air pumps, gas turbines, etc).

Japan’s exports are machines (37%), transportation (22%), metals (9.8%), chemicals (8.5%), and instruments (7.8%). Or, in more detail: cars, vehicle parts, integrated circuits, and a variety of machines like industrial printers.

South Korea’s exports are machines (37%), transportation (19%), minerals (8.9%), metals (8.5%), plastics (7.1%). In more detail, integrated circuits, phones, cars, ships, vehicle parts, broadcasting equipment, and petroleum.

“Heavy industry” — that is, machines, engineering, automobiles, electronics, and metals — is the cornerstone of an industrial economy. Integrated circuits are a true “root” of the tech tree, the foundation on which the information economy is built. Capital-intensive heavy industries like automobiles are a “keystone” which is deeply interwoven with the production of machines, parts, robots, electronics, and steel.

It’s a relevant warning sign for Americans that many current developments that seem likely to improve “heavy industry” are _not _concentrated in the US.

Of the top 5 semiconductor companies, only 2 are American. Some electronics innovations, like flat-screens (developed by Sony) and laser TV’s (developed by LG) were developed by Asian companies, and Mexico is the biggest exporter of flat screen TVs. Robotics, as discussed above, is being pursued much more intensively in Asia and Europe than in the US. “Smart factories”, in which automation, sensors, and QA data analysis are integrated seamlessly, are being pioneered in Germany by Siemens. The majority of drones worldwide are produced by Israel. The Japanese companies Canon and Ricoh, as well as the American HP, are expected to launch 3d printers this year; meanwhile the largest manufacturer of desktop 3d printers, XYZprinting, is Taiwanese.

A positive sign, from a US-centric perspective, is that self-driving cars are being developed by American companies (Tesla and Google.) Another positive sign is that basic research in physics and materials science — the fundamentals that make a continuation of Moore’s law possible — is still quite concentrated in American universities.

But, to have a strong industrial economy, it’s not enough to be good at software and basic research; it remains important to make machines.

Non-xenophobic, economically literate, pro-industry

Globalization has been a humanitarian triumph; Asia’s new prosperity has vastly reduced global poverty in recent decades. To acknowledge that global competition has been hard on Americans doesn’t preclude appreciating that it’s been good for foreigners, and that foreigners have equal moral worth to ourselves.

Acknowledging harms from trade also doesn’t require one to be a fan of planned economies or a believer in a “zero-sum world.” Trade is always locally a win-win; restricting it always has costs. _But _it may also be true that short-term gains from trade can be counterweighted by long-term losses in productivity, especially due to loss of the gains in local skill and knowledge that come from being a manufacturing center.

If you want to live in a vibrantly growing country, you have to make sure it remains a place where things are made.

That’s not mere protectionism, and it’s certainly not Luddite.

I don’t think this is true of, say, agriculture, where vast increases in efficiency have reduced the number of farmers needed to support the global population, but where that’s not really a problem for overall growth. US farming has not _lost ground — we produce more food than ever. We are not getting _worse at farming, _we just need fewer people to do it. I suspect we are getting _worse at manufacturing. And since manufacturing has so disproportionate an effect on downstream growth and innovation, that’s a problem for all of us, in a way that it’s _not _a problem if farmers or travel agents lose their jobs to new technologies.

Pro-Industry, Anti-Corruption

The truly obvious gains from capitalism are actually gains from industry. Cheap, varied, abundant food. Electricity and electric appliances. Fast transportation. The sort of things described in Landsailor.

Other things that show up in GDP are less obviously good for humans. If real estate prices rise, are we really better housed? If stock prices rise, do we really have more stuff? If we spend more on medicine and education but don’t have better health outcomes or educational outcomes, are we really better cared for and better educated?

The value of firms has dramatically shifted, since 1975, towards the “dark matter” of intangibles — things like brands, customer goodwill, regulatory favoritism, company culture, and other things that can’t be easily measured or copied. US S&P 500 firms are now 5/6’ths dark matter. How much of the growth in their value really corresponds to getting better at making stuff? And how much of it is something more like “accounting formalism” or “corruption”?

If you are suspicious of things that cost more money but don’t create obvious Good Things for humans, then you will _not _consider a shift to a service economy a good outcome, even if formally it doesn’t look too bad in GDP terms. If you take a jaundiced view of medicine, education, the “helping” professions, government, and management — if you see them as frequently doing expensive but unhelpful things — then it is _not _good news if these sectors grow while manufacturing declines.

If your ideal vision of the future is a science-fiction one, where we cure new diseases, find new fuel sources, and colonize the solar system, then _manufacturing is really important. _

The old slogans like “what’s good for GM is good for America” are not as far from the truth as you’d think.